The Language of Islamic Architecture

In Islam, man is a social being entrusted with a noble mission of responsibly inhabiting and developing the earth (vicegerency or khilafah). He is endowed with enough appropriate at once ingenious and executive capacities for the attainment of the former. Proportionate to the intrinsic character of man and his aspirations and undertakings, his terrestrial calling takes account of all the planes of physical and metaphysical existence. The net result of such a mission is always bound to be cultures and civilizations that typify and reverberate the profundity and wholesomeness of the causes and influences that engendered and gave rise to them. Man’s life, accordingly, is all about forging and nurturing relationships, starting with his own self and then with all the other existing spiritual and material, animate and inanimate, realities, and all the way through the horizontal and vertical miscellaneous levels and dimensions of life. It is due to this that man in Arabic is called insan, which is derived from the verbs anisa and ista’nasa which mean: keep someone company, feel at ease with someone or something, get used to, and to become friendly and benign towards others. Total isolation and loneliness would thus always be an excruciating chastisement for man. This is so because that way, man will not be himself, or herself, and whatever he, or she, does in such a state will prove unnatural and against his, or her, primordial penchants and physical as well as mental and spiritual configuration, and so, detrimental to his, or her, overall wellbeing.

This also means that man must interact and communicate, and that his interactions and communications must transcend the sheer levels of superficiality, frivolity and one-dimensionality. Hence, as soon as God created Adam, the father of mankind, He taught him all the names (of everything) (al-Baqarah, 31), that is, the names, the properties, the inner natures and qualities of all the existents. In other words, Adam was taught the words, identities and meanings of everything and how to express and articulate his thoughts and feelings concerning them, as well as how to form relationships with them based on proper communications and understanding, rather than miscommunications, misunderstandings and confusion. Adam was made to perfectly understand the world and to be perfectly understood by it, which stood for the most fundamental facility and resource required for successfully discharging his life assignments. Put simply, Adam was taught a language, but not only insofar as the phonology, morphology and syntax aspects thereof were concerned, but also, and more importantly, as regards the notions of intelligent and wise speech and communications and how they should become instrumental in expressing and serving a higher transcendental order of things, ideas and meanings. That said, for example, a person may know a language: its alphabet, words and even its grammar and syntax, but that in no way automatically qualifies him, or her, as a good writer, a poet, or an orator. Much deeper understanding and knowledge, plus a special aptitude and forte, are needed for those purposes.

Certainly, it is because of this verity that God says in the Qur’an in the al-Rahman chapter: “He has created man; He has taught him speech (and intelligence)” (al-Rahman, 3-4). The word used for speech and intelligence is bayan which generally means: an act of explaining and showing how something works or is done, explanation, illustration, elucidation, making something clear, action or process of expressing, proclamation, eloquence, etc. According to Abdullah Yusuf Ali, bayan means: “intelligent speech, power of expression, capacity to understand clearly the relation of things and to explain them. Allah has given this to man, and besides this revelation in man's own heart, has aided him with revelation in nature and revelation through prophets and messengers.” The above-mentioned verses are preceded by these two verses: “(Allah) Most Gracious. It is He Who has (taught) the Qur’an” (al-Rahman, 1-2), which could be interpreted along the lines of God’s universal and infinite mercy part of which is His endowing man with the gifts of languages and his vast potentials to think, interact and communicate, as well as along the lines of the Qur’an and other revealed scriptures denoting the best inspiration, source and guidance in man’s application of his emotional, cognitive and communicational predispositions. As if the third and fourth verses have been both illuminated and conditioned by the first and second ones.

The phenomenon of languages, it goes without saying, is in itself a divine sign meant to be a tool through which man can understand, internalize and communicate the rest of divine conceptual and actual physical portents. Through proper and purposeful use of languages, man unambiguously showcases his ontological worth and direction. Languages are propellers of a cultural and civilizational sophistication and finesse, for people, indeed, are what and how they speak, and in what manner they act upon it. Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) once said to one of his Companions, Mu’adh b. Jabal: “Should I not direct you to the highest level of this matter (living like a faithful devotee), to the pillar on which (it rests) and its top?” Mu’adh said: “Allah’s Messenger yes, (do tell me).” He said: “The uppermost level of the matter is Islam. Its pillar is the prayer and its top is Jihad.” He then said: “Should I not inform you of the sheet anchor of all this?” Mu’adh said: “Allah’s Apostle (of course do it).” He took hold of his tongue and said: “Exercise restraint on it.” Mu’adh said: “Apostle of Allah, would we be held responsible for what we say with it?” Thereupon he said: “Mu’adh, may your mother be bereaved. Will anything else besides (irresponsible and sinful) talk cause the people to be thrown into the Hell-Fire upon their faces or on their nostrils?” (Jami’ al-Tirmidhi).

On account of its complex nature and multifaceted significance, which is not only a privilege of man and a hallmark of his civilizational output, but also a key constituent in every other existential realm, or world, the language phenomenon, on the whole, could be viewed through the prism of two major concerns. In its conventional sense, language is a system for the expression of thoughts, feelings, values, etc., by the use of spoken sounds common to a people of the same community or nation, the same geographical area, or the same cultural tradition, which is the subject of the science of linguistics. Moreover, a language is also any other systematic or nonsystematic means of communicating by means other than a body of words and the systems for their use, such as conventional symbols, representations, gesticulation, revelations, portents and even animal sounds; a particular manner or style of verbal expression; a specialized vocabulary developed and used by a particular group bound by common interests; the means and systems of intelligent, emotional and spiritual communications – uniform and systematic, or otherwise – comprehensible to certain groups or categories of people.

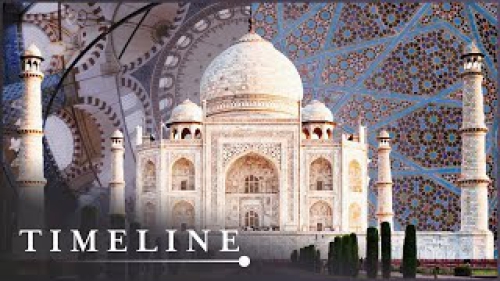

By virtue of being man’s third skin, so to speak, and both a framework for and a mirror of his out-and-out life activities -- to the extent that it has become synonymous with the worth and dynamism of human presence and activism on earth -- architecture more than a majority of other life pursuits is qualified to evolve its own systems of physical and metaphysical expressions and communications, partly or completely. This applies to the sphere of Islamic architecture, too, even though, in essence, it shuns literal symbolism, blind imitation and following, and that the form is glorified at the expense of function.

In its capacity as art and so, an object, generator and depository – all at once -- of beauty, Islamic architecture and its remarkable aesthetic appeal correspond to the splendor of truth -- to rephrase Plato’s proclamation that “beauty is the splendor of truth”. It is also an expression of Islamic teachings and values and a soul of Islamic culture and civilization. As a science and engineering, on the other hand, Islamic architecture centers on designing, building and using interior and exterior spaces, providing thereby a material theater to Muslims to practice and live Islam as a comprehensive way of life. Islamic architecture, thus, implies furnishing Muslims with built environment and material development facilities and solutions, inspired by and incessantly in agreement with the implications of the permanent worldview and normative teachings and traditions of Islam, as well as with the implications of the vicissitudes of daily life. Islamic architecture though planted in and governed by the parameters of different times and geographic spaces, is timeless. It subtly rises above the perennial dialectics of the relationship between the form and function. In its vast domains, the form and function are one, “joined in a spiritual union” -- to draw on the words of Frank Lloyd Wright who said so in the context of his general understanding and appreciation of architecture.

As such, authentic Islamic architecture has much to say, and does so eloquently. This is so because, aside from functioning as a container, a physical locus and so, a discernible sign of Islam and Muslims’ lives, and aside from its goal to create spaces that will enfold, embrace and stimulate the persons in them, Islamic architecture also aids man in living out his dignified terrestrial mission by providing facilities and services, and by inspiring, promoting and communicating its and Islam’s refined philosophy and purpose. In other words, Islamic architecture is at once a field and means of silent, yet overwhelming, da’wah islamiyyah (promoting and preaching Islam). It captivates human sensitivity and emotions possibly more than any other segment of culture and civilization. It acts slowly, but most surely, both on the mind and soul.

However, for one to understand Islamic architecture one needs to be familiar with its conceptual and functional lexis and meanings; one ought to comprehend its soul and grand purpose, lest miscommunications and confusion should emerge and persist. To begin with, seeking prescribed and uniform formal Islamic architectural concepts will lead a researcher nowhere because there is virtually none. Even in the field of mosque architecture, where the quintessence of Islamic architecture is perhaps most powerfully expressed, and where the focus of the search of most people, as a result, is, there is no even single official and rigid architectural concept and element -- at best, there is extremely little -- to be found either. And this is exactly where the core of the major problems lies, and whence almost all misunderstandings and miscommunications between Islamic architecture and many of its users, observers and students originate. Principally, the problem was created and gradually exacerbated by the exhaustive studies of Islamic architecture at the hands of the Western scholars and their Muslim collaborators who, while operating within the context of prolonged processes of colonization and westernization of the Muslim lands, indigenous cultures and, most perilously, minds and thoughts, failed in their scrutiny and assessment of Islamic architecture’s genuine significance and value.

On that note, Isma’il al-Faruqi strongly criticized the Western scholars of Islamic art and architecture in their failure to evaluate the latter’s real meaning and worth, despite their exhausting application to the task of studying, collecting and systematizing the same into art and architecture schools and styles. The root cause of the problem was that Islamic art and architecture were viewed and examined through the lens of the standards and criteria of the Western art and architecture with their ubiquitous materialistic, naturalistic and humanistic underpinnings. Isma’il al-Faruqi thus wrote: “Nobody can survey the field without being struck by the Western scholars’ arduous application to the task, without falling in admiration of and gratitude for their legacy of scholarship and museum-achievements. There is no road to the serious study of Islamic art except through their works; and there is as yet no library of Islamic art in which these works do not constitute the overwhelming majority. And yet, the Western scholars of Islamic art have been unfair in their overall assessment of its real value. For all their self-application, their seriousness and brilliance, their hard work and perseverance, they have failed in the supreme effort of understanding the spirit of that art, of discovering and analyzing its Islamicness. For lack of any such understanding, they fell upon the spirit of their own art (i.e. Western art) and, armed with that spirit as absolute norm of all art, they sought to bend Islamic art to its categories. And, when Islamic art naturally refused to be so bent, their misunderstanding of it deepened. The charge they imputed to Islamic art was always the same, namely, that it had failed in that in which their Western art had excelled and almost everyone repeated the charge.”

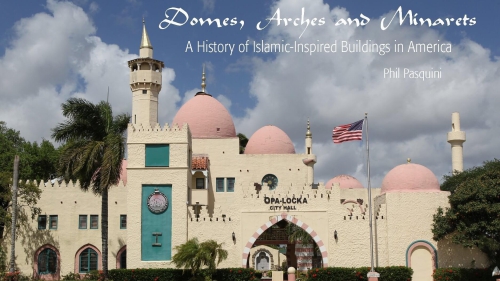

The language of Islamic architecture, therefore, is not to be found exclusively in the world of physical architectural and engineering manifestations. By no means are arches, domes, minarets, praying niches, pulpits, courtyards, colonnades, parapets, muqarnases or stalactite-like decorations, mashrabiyyahs and other forms of apertures screenings, calligraphic inscriptions, geometric patterns, etc., permanent and prescribed constituents of the vocabulary of Islamic architecture. Rather, the eternal and prescribed language of true Islamic architecture is spiritual. It accounts for all those Islamic principles and values and elements of the Islamic worldview and belief system which dictate the ways Muslims forge and cultivate a delicate network of life relationships, and how they interfere with and impose their regulated vicegerency motives and will onto the realms of other existential realities. As regards Islamic architecture’s physical manifestations and styles, however, they predicate mere rendition and translation of the former into fluctuating time-space contexts. Furthermore, they are to be perceived as no more than creative and effective solutions and answers to the quandaries posed by the prospect of dynamic application of the transcendent Islamic message into the vicissitudes of life. Many of those physical architectural solutions and answers were often repeated -- albeit with regular revisions, modifications and improvements, subject to the state and availability of building technology, engineering and local talent -- as they were dealt with in similar and recurring life circumstances, in that, definitely, what was good and functional in a time and space, should be reasonably likewise in another identical times and spaces. There was nothing technically wrong with this life pattern because it constituted a part of sunnatullah. For example, many Muslims in many dissimilar geographical regions eventually became fond of employing, to various degrees, arches, domes, domestic and institutional courtyards, mashrabiyyahs, colonnaded especially public spaces, roof parapets, crenellations or merlons, calligraphic inscriptions, elaborate arabesques, geometric patterns, etc., not because such represented the uniform language of Islamic architecture, but because such proved time and again a very effective, expedient and suitable foundation for satisfying their subtle aesthetic taste, and for facilitating their every day religious, cultural and socio-economic affairs and activities both as Muslims and residents of those geographical regions. That is to say, they were functional and at the same time compatible with Muslims’ spiritual, socio-cultural and artistic remarkable consciousness and zeal. Certainly, it would be a serious epistemological blunder if all that is taken in as a prescribed and inflexible language of Islamic architecture. So serious would the error be that it will have a potential to blind people’s perceptive faculties and incapacitate them from rising above the world of matter and make them penetrate the orb of metaphysical ideas and meanings. As a matter of fact, it is of the ABCs, or rudiments, of Islamic architecture to affirm that Islam and its integrated cultural systems fashioned the whole way of life by providing a template of behavioral archetypes which, by necessity, generated correlated physical patterns, as stressed by Stefano Bianca. “Therefore, the religious and social universe of Islam must be addressed before engaging in the analysis of architectural structures.”

Thus, freely and tentatively defined, the language of Islamic architecture would be a systematic means of communicating ideas, values and feelings by the use of relatively conventionalized architectural ingenious design solutions, elements, features, gestures, intents and purposes. The fundamental components of such a language, which under the influence of different life conditions translate themselves in different ways onto the level of architectural physical expressions, will revolve around the themes of how Muslims deal with and overcome the challenges posed by the subject of respecting and protecting privacy within both the private and institutional spaces; how the buildings of Muslims accommodate and facilitate the discharging of their religious ceremonies and socio-cultural activities; how Muslim architectural models, while enclosing, cuddling and exalting the interior spaces, continue to interact with the outer space for lighting, ventilation and for some other ontological reasons in that space is commonly perceived in the worldview of Islam as part of God’s creation and a theater for His divine Will and Plan; how imaginatively and resourcefully Muslim artistic and architectural consciousness respond to the Islamic tenet that God is beautiful and loves beauty; how the honor, dignity, unity, freedom and basic human rights of all people -- in particular immediate and distant family members, neighbors and fellow Muslims -- have been upheld and propagated; how Muslim buildings are made eco-friendly and sustainable so as to render them in full agreement with the Islamic notion that the earth has been entrusted to man in order to dutifully develop and sustain it, as well as with the idea of maqasid al-shari’ah (the objectives of Islam and its shari’ah or law) according to which man’s life (al-hayah), spiritual primordial inclination (al-din), mental power (al-‘aql), the wellbeing of future generations (al-nasl), and the resources and wealth of individuals, institutions, countries and the whole earth (al-mal) are to be preserved at all costs; how genuine Muslim architectural inventiveness says a big “No” to extravagance, squandering, haughtiness, self-centeredness, corruption and other major vices directly or indirectly associated with the enterprise of building, and a big “Yes” to moderation, prudence, unassuming nature, altruism, honesty, accountability and other major virtues that are linked with the processes of architecture and building; how Islamic architecture adopts comprehensive excellence as its vision and performance benchmark, determinedly rejecting deliberate mediocrity and ineptitude; how the essence of Islamic architecture simultaneously esteems and humbles, stimulates and reminds, rewards and cautions man as mere God’s creation, servant and trustee on earth, but ceaselessly and totally exalts, acclaims and deifies God as the only Creator, Lord, Master and Sustainer of the whole universe, thereby rejecting in most resolute terms the prospect of espousing the materialistic, naturalistic and humanistic underpinnings of certain Western and other similar architectural styles and schools of thought.

However, for the language of Islamic architecture and its sophisticated meanings to be aptly constructed, articulated and understood, appropriate and lifelong educational literacy programs and services ought to be made available, first and foremost, for Muslim designers and architects – and the rest of directly and indirectly related professionals – in their capacity as the language of Islamic architecture primary makers, developers, sustainers and its most immediate advocates and communicators. Next come the lifelong educational and literacy agendas for the public as those who order and procure, patronize and benefit from Islamic architecture, and as those whom the language of Islamic architecture targets, and to whom it communicates, first. Indeed, it becomes very obvious how crucial the role of Muslim educational systems in general and the role of Muslim architectural education in particular, is in the Muslim countries. Such educational systems must strive to live up to the requirements and implications of the universal and all-encompassing Qur’anic message of iqra’ bismi rabbika (“Read, recite and study in the name of your Lord…”) (al-‘Alaq, 1-2). They must teach and prime Muslim generations to audaciously tackle head-on all life challenges, and to honorably and responsibly live and contribute as true stewards of God’s earth.

Since the religion of Islam is the foundation and moral fiber of Islamic architecture, Islam likewise is to be the foundation and moral fiber of Muslim architectural educational systems. It is only with a genuine Islamic mindset, passion and purpose that Islamic architecture can be revitalized and restored. It is only with the same state of mind and soul that Islamic architecture can be truly understood and treasured. Thus, Muslim educational systems must aim to produce generations whose members will be acquainted with, feel affection for, practice, care and live for Islam: its ideology, peoples, history, culture and civilization. Only in such a dynamic, conducive and engaging spiritual and intellectual environment, genuine Islamic architecture is, and can be, constructed, taught, learned and valued. Muslim educational systems, on the whole, must produce honorable, moral and visionary men and women, rather than materialistic, disoriented and superficially cultured professionals and citizens.

Muslim educational systems, further, should not produce spiritually illiterate and blind students who will fall short of seeing and comprehending the meaning of their own cultures and civilization, let alone initiating, generating and promoting to the world some of their constituents. And when it comes to Islamic architecture, the Muslim mind, heart and soul, principally, need be fully awaken and made receptive to its spiritual, emotional and intellectual outpouring and aura, for it was the spiritual, emotional and intellectual hankering that envisioned, formed and articulated it in space. It goes without saying, therefore, that the purified and enlightened hearts, minds and souls are targeted and sought out first and most in Islamic architecture. For that reason, Muslims should not find themselves on the receiving end of the Qur’anic words to the effect that there are people who “have hearts with which they do not understand, they have eyes with which they do not see, and they have ears with which they do not hear…” (al-A’raf, 179). Also: “For indeed it is not the eyes that grow blind, but it is the hearts, which are within the bosoms, that grow blind” (al-Hajj, 46). Alternatively said, a kind of a sixth sense anchored in Islamic spiritual discernment and wisdom is to be yielded and incubated. Worldly greatness and wisdom are not good enough as they do not go with the required spiritual insight.

Last but not least, the language of Islamic architecture -- accounting for both the processes and net products of planning, designing and constructing buildings, as well as their ultimate performances and uses -- is universal, consistent with the universality of the Islamic message which it embodies and communicates to its immediate users and beyond. Its physical alphabet or vocabulary was never meant to be prescribed, for, surely, no predetermined temporal architectural style or school of thought is capable of containing all the spiritual and intellectual dimensions and aspects of the Islamic architecture universe, regardless of how rich, sophisticated and advanced it might be. Such a language then needs to be dynamic, fluid and open-ended, always calling for novel ideas, solutions and protagonists. Just as no age or geographical space could completely grasp and present it, similarly no nation or demographic group could ever claim its ownership either.

The authentic, and in reality infinite, language of Islamic architecture needs incessantly to evolve with different times and different socio-economic groups which will contribute their respective shares to its qualified materialization. The quintessence of Islamic architecture is thus rightly described as unity in diversity, namely, the unity of origins, message and purpose, and the diversity of styles, expressions, methods and solutions. It is also an enthralling amalgamation of spirit and matter, and of the heavens and the earth. Islamic architecture is a constant collective Muslim attempt to bring as closely, and as evocatively, as possible sets of pertinent Islamic principles, values and ideals from the realm of philosophical, prescriptive and abstract ideas to the world of tangible and concrete realities. Such, however, is intrinsically an impossible task, so collective attempts must go on indefinitely. Additional appropriate ways and methods are always to be sought, so as to keep enhancing and enriching with the passage of time the Islamic architectural legacies. As a result, there should never be slowing down of Islamic architecture’s dynamism, progressiveness, ingenuity and inventiveness. Just as there should never be slowing down, much less stopping, of the boosting and augmenting of the language of Islamic architecture. Together with blind following and imitation of others, that could even be regarded as an architectural crime resulting from a dangerous level of architectural illiteracy.

Topics: Islamic Art And Architecture, Islamic Housing

Views: 3306

Related Suggestions