Islamizing and Teaching Housing

Islamic housing, as a concept and sensory reality, signifies a microcosm of Islamic culture and civilization. It is where the epicenter of the rise and fall of Islamic culture and civilization lies as it represents the ground for living and practicing some of the most critical segments of human existence and, as such, some of the most critical segments of the Islamic message in its capacity as a total philosophy and a way of life. This paper seeks to enhance the awareness, both of the professionals and general readership, as to the significance of correctly conceptualizing Islamic housing. It also seeks to increase people's awareness about Islamic architecture, and the whole of Islamic built environment, on account of Islamic housing representing the most vital aspect of Islamic built environment. It is an embodiment and soul of the latter.

While Islamizing the notion of housing both in theory and practice, as a matter of great urgency and a remedial measure, Muslim architects, planners and engineers can draw on their own familiarity with the rulings of Islam, provided the same is adequate. Otherwise, trustworthy religious scholars, who are both qualified and broad-minded, should be consulted and engaged as many times as needed. Even as professional advisors and consultants some religious scholars could be appointed either by the government or by private firms and establishments. It goes without saying that unremitting inter and cross-professional housing studies and research activities appear to be inevitable. This is bound to lead gradually to narrowing down the glaring gap separating the religious scholars and their fields of interest from the secular ones and their own fields of interest. This way, every scholar will become aware as to his/her role in society and his/her obligations toward society, nature and Allah. Certainly, the religious scholars will have to widen their interests and concerns, becoming what they are actually always meant to be: the guardians of societies. But to secure that accolade they ought to reevaluate themselves and their undertakings, striving to be a more practical, approachable, people-friendly, and less dogmatic and idealistic lot. Whereas the secular scholars will have to think of Islamizing their knowledge, wherever there is a conflict of interests and as much as possible, realigning their scientific goals and aspirations with the goals and aspirations of Islam and the Muslim community to which they belong.

Definitely, it is a high time that a serious and scientific initiative of integrating the Islamic worldview, ethics and value system into residential planning and architecture takes off in the Muslim world. However, such a scheme is to be only a segment of a broader Islamization project which will aim to bring about a total harmonization between the education systems of Muslims and the teachings and values of Islam. It is not that residential planning and architecture should be only targeted by this scheme, but also the whole of built environment professions. The process of integration between built environment professions and Islam will yield best results if it were embarked on wisely and gradually, after the people: policy makers, built environment professionals and users, have become convinced of its relevance and urgency, and that they all must as much contribute to as they benefit from it, and even more.

As a beginning, in universities and colleges where students undertake planning, design and architecture programs and where a strong emphasis on housing issues is made, some in-depth and deemed most needed programs on Islamic studies can be taught. Lecturers and tutors will have to be well-educated, well-trained and will have to lead by example. Their role will be critical. The mission of Islamization is a massive and complex one so students will always look up at their teachers for inspiration and guidance.

The programs can be taught independently, or they can be integrated into the syllabus of other courses. The latter option is the finest one, as it is spontaneous and natural, hence more effective. Due to the obvious relevance and applicability of the integrated subject matter, the students will have little or no reasons to develop any aversion to what they are subjected to. The former option, however, if applied alone is not really an effectual one, as it is suggestive, nominally though, of perpetuating the existing rift between the religious and planning and architectural sciences. At best, the same can be seen as just an addendum to the existing curriculum, to which the students are bound to develop much indifference.

Unquestionably, the best and most workable solution would be a viable combination of both options. In the process, either option can be given more emphasis at the expense of the other, subject to the dictates of different situations. However, regardless of what model is eventually developed, this aspect of Islamization process can become effective only if students are constantly urged to incorporate what they have learned in the classroom into their practical works in studios and laboratories. Above all this, furthermore, intensive workshops, seminars and trainings on Islamic housing can be periodically organized for those who have already graduated and are actively and professionally involved in the housing sector, so that continuity is ensured and if considered necessary with some professionals, enthusiasm for the mission renewed.

It would be even better if the education systems of Muslims are such that all students come to colleges and universities with a reasonable amount of knowledge about Islam and its culture and history, which they have obtained beforehand at the lower levels of their study. What would then transpire in colleges and universities -- where the curriculum, teaching methods, references and the knowledge of the lecturers and tutors are expectedly all Islam compliant -- is that no time will be wasted on clarifying basic concepts and on dealing with introductory issues. Rather, straight from the beginning the core issues in Islamic housing could be seriously approached from perspectives that suite the level of students' study, aptitude and interests. It could be then hoped that within the prescribed timeframe which students spend in colleges and universities, a significant set of objectives with respect to Islamization and integration of knowledge in the housing sector can be successfully achieved. Then, the whole enterprise will in due time become a serious, sought-after and productive scientific project, rather than a superficial, superfluous and decorative addendum and diversion.

In universities and colleges the students can be taught some independent courses on the belief system ('aqidah), ethics (akhlaq), traditions, culture (thaqafah) and history of Islam. However, this will have little or no impact if the same knowledge is not referred to and is not attempted to be applied in those subjects which are directly linked with the question of housing as society's biggest concern, focusing on its historical, theoretical, cultural, aesthetic, religious, ethical and environmental dimensions.

For example, in an independent Islamic course the students are expected to thoroughly learn about the position of Islam on peaceful coexistence with the environment. Apart from the theoretical part, a lecturer in the same course must be ready to stir up the thoughts of students through a discussion, an assignment, or a question in a test, towards the practical implications of that particular theme -- to which Islam, not by an accident, attaches so much importance -- for planning, designing and building houses. Next, in the studio where the students might be asked, for example, to plan an environment friendly neighborhood, or design an energy efficient or sustainable house, the environmental lessons learnt beforehand in an independent Islamic course should serve to the students as the foundation, inspiration and chief guidance in their works. The studio lecturers, in turn, are expected to be very familiar with the same lessons -- at best that those lessons make up the core of their own environmental education -- looking forward to seeing the students ingeniously apply those environmental lessons in their planning and design final products which can be called, for example, "an Islamic environment friendly neighborhood", or "an Islamic energy efficient house", or "an Islamic sustainable house".

Similar methods are to be devised and applied to the integration of the rest of the Islamic teachings and values which underpin the idea of housing in Islam, into the Islamic housing education. Indeed, for the Islamization of the housing education, the students and lecturers must work closely as a team, helping, supporting, encouraging and learning from each other, while relying on, and deriving the strength from, the oneness of their divinely sanctioned life vision, mission, purpose, objectives and knowledge sources.

Presently, the housing planning and building education in the Muslim world, by and large, is very heterogenic in terms of its historical, theoretical, philosophical and cultural propensity and substance. Unfortunately, one has got to believe that there is no clear sense of purpose and direction, which is always the case when blindly following others, in this case the West, becomes a trend. Undeniably, Islam and its cultural and civilizational perspectives are still there, however, they are choking under the constant pressure of the other willingly imported perspectives and options. Partly due to this, and partly due to the glaring lack of a political and decision-making will, it will be very difficult for Islamic housing to institute and ascertain itself. The current overall climate is unfavorable for a dramatic change to take place in a foreseeable future.

As far as the relationship between the Islamic and other housing perspectives in Muslim universities and colleges is concerned, the most ideal scenario will be that the lecturers and tutors whenever dwelling on any of the housing aspects, either in theory or practice, give a clear and comprehensive overview of the topics discussed firstly from an Islamic perspective, as the one to which both the lecturers and students faithfully subscribe, trying then to incorporate the clearly presented Islamic input into the practical works on housing. This process could be supplemented by occasional and brief references to some other cultural, historical, religious, philosophical and environmental perspectives on housing, but only for the sake of student exposure, comparative studies, and the broadening and enriching of the student minds, and not for the sake of becoming suspicious of the Islamic perspective's place and validity and for the sake of possibly abandoning and bartering it in favor of a foreign perspective.

Two major challenges

However, there remain two main challenges to be overcome.

Firstly, there is a problem of educational systems and educators from the level of policy and system making and implementation to the level of training and teaching. Most of the personnel involved have obtained their education under the systems, locally or abroad, that do not recognize the Islamic perspective in housing - and in the whole of the built environment - as a potential and viable one. The Islamic perspective, even if somewhat deemed as an option, is still regarded by many as inferior, of a lesser value, and not on an equal footing with other housing planning and building perspectives.

Since the systems and the personnel behind them, as well as the educators, signify the richest and most important source of knowledge and wisdom to the students, there could be no many significant changes, it goes without saying, until the situation improves at its source(s). The policy makers and implementers, lecturers, tutors and trainers, to a large extent, account for the most immediate cause of the predicament facing the Islamic housing education in Muslim universities and colleges, as much as they can become the most immediate agents of change and the most direct cause of any paradigm shift aimed at the improvement of the situation.

The second challenge is one of the housing planning and building curriculum and literature which, too, have been tailored and produced in Muslim universities and colleges least of all according to the Islamic perspectives. This way, everything seems to be set for the perpetuation of the separation of the future Muslim professionals in the built environment from their true identity, culture and history. Thus, even if the level of Islamic awareness of some lecturers, tutors and students is remarkably high, they still cannot completely live, learn and operate away from the influences of the philosophical and empirical perspectives, some of which are neutral, but some of which are plainly contradictory and conflicting, insofar as the Islamic worldview and its value systems are concerned. This is so because the curriculum which those Muslim lecturers, tutors and students have subjected themselves to, and the literature which their curriculum feeds and depends on, originate from the same philosophical and empirical perspectives which they wish to disentangle themselves from. So depressing is the state of affairs that a person, especially from amongst the young ones, those with fragile minds, may simply lose his heart and end up believing that he is faced with a lose-lose situation. The best option that is left, one may think with an intellectual resignation, is to try and choose from the two predicaments a smaller and less painful one. Trapped in this vicious cycle, the Muslim mind can hardly free itself from its clutching fetters and burst through its inhibiting sway and authority, setting then out to contrive in line with its own preferences some feasible and more adequate and acceptable alternatives.

Central to the encountering and overcoming of the second challenge is the production of Islamic books and references on housing. They will counter and substitute those books and references which with their contents, ideas and interpretations tend to confuse and keep the Muslim students at bay from their authentic Islamic identity, culture and history. Some of those books with some of their malicious contents even manage to indoctrinate those young Muslims minds which are poorly grounded in Islam against themselves and their Islam.

As an example, there are people who believe that the four-square arrangement of rooms around a central domestic courtyard, which is the most conventional plan in many traditional Islamic houses, reflects the fact that a Muslim may marry as many as four wives. "In this case, each wing of the house must constitute a separate dwelling, for each of his wives is entitled to equal treatment; she must be able to receive her husband in her own home, and he must be the guest in turn of each of his several wives according to strictly formulated rules or, more exactly, according to the Prophet's example whose fairness and generosity to his wives is the model to be emulated." (Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam, p. 191)

This belief is not totally baseless, though, as the Muslim men indeed may marry up to four wives and courtyard houses are perhaps the most ideal type for a large family in terms of convenience and smooth interaction among family members. Bu to single out polygamy as the only reason, or as one of a very few reasons, for having courtyards on such a large scale in Islamic domestic architecture, failing to see sets of splendid Islamic values and principles which, in fact, called for their existence, would be a serious scientific, intellectual, and for Muslims, spiritual shortcoming.

Moreover, Islamic houses are sometimes depicted as "harems" (places for engaging in physical pleasures); as "prisons" in that many housing types, at a first glance, appear as though unable to receive any light from the street because they have no windows on their outside facades; as places meant for the total seclusion of women because their position and roles have nothing to do with the outside world; as intended images of Paradise (Jannah) in which case the house plans and designs are heavily loaded with needless literal symbolism, etc.

Successfully dealing with the second challenge, in particular, will be conditioned by the creation of a strong, excellent and all-pervading research culture on a variety of issues in relation to the subject of Islamic housing. A salient feature of such a culture will always be the encouraging, promoting and heavily investing in original, creative, critical, universal, unprejudiced and tolerant thinking. This means that each and every Muslim housing and built environment educator, supported by each and every Muslim housing professional on the field, cannot afford to turn his or her back to, and thus perpetuate, the present dismal scenario in the field of Islamic housing education by failing to grasp the extent of the problem and then fail to contribute his or her share to its improvement.

Being educated, sometimes to the highest possible level and in the best of the world's educational institutions and establishments, implies that much has been invested in Muslim educators and professionals. They must give something back to their religion and society. Investments must be paid back. Holding a Master's or a PhD degree today in the Muslim world, for example, is not a privilege; rather, it is a burden and responsibility. Such becomes a mark of distinction only when society is duly served. It is not only about selfishly taking for one's self; it is about selflessly giving back to others as well. Ignoring the intellectual and spiritual plights, as well as the silent pleas, of their societies and peoples, after they had managed it to the top, often at the expense of societal and public resources, such actions of Muslim educators and professionals will be tantamount to betraying their people, society, culture and religion.

An illustration of this type of social betrayal is that a Muslim educator while teaching his students a course on housing - or some other relevant courses - uses constantly a reference book which contains elements that explicitly contradict the message of Islam. In doing so, the educator, maybe, fails to notice the problems, so he misleads his self and others. Or he notices them but fails to act and adequately address them, thus failing to properly warn the students and equip them with what it takes to deal with the problems at hand. Laziness, indifference and apathy eventually get the better of him. Despite all this, however, the educator never even bothers, let alone undertakes some constructive initiatives and some concrete steps, to come up, alone or with someone else, as a result of his own research activities or someone else's, with more acceptable and more compatible with the Muslim spirit and mind alternatives as a subject's main references. The educator thus betrays two trusts which have been placed on his shoulders: the trust of knowledge and the trust of students.

Therefore, it is incumbent upon each and every Muslim educator, in particular, to contribute greatly to cleansing and enriching the existing curriculum and its literature on Islamic housing education in their universities and colleges by producing quality research papers, articles and books on the subject, and then by disseminating the same to the students and colleagues in the classrooms, studios and during the academic meetings, seminars and conferences, locally and internationally. These contributions are never to dwindle, or end, as the road to a global Muslim intellectual and spiritual recovery is long and challenges lying ahead immense and numerous. Intellectual mediocrity, lethargy and indifference in the arena of Islamic housing, and the Islamic built environment in general, it follows, are serious crimes with some far reaching consequences for the wellbeing of Muslims. Intellectual self-centeredness, selfishness and greed are equally repulsive in Islam with equally detrimental impact and consequence.

At any rate, however, it all boils down to the systems of education that the Muslim community adopts, and to what extent the same community is ready and willing to embrace that which is best for preserving its housing identity and reinvigorating its cultural and civilization prospects. Indeed, it is essential that people start realizing that by creating houses a framework for much of their lives is created. To a large extent, people's lives are thus dictated and influenced. Hence, the two, i.e., the framework with its character and services and the exigencies of people's lives, must be compatible.

It is very difficult to live delightfully, honoring and applying the teachings and values of Islam, in a residential architectural world that is alien to the same teachings and values and their divine philosophy. It is only when compatibility between the two poles exists that people's actual interests and welfare will be ensured, and that residential planning and architecture will become more than just a process of planning, designing and erecting houses. Indeed, there is much more to Islamic housing than just that, that is, than the physical aspect of the whole thing.

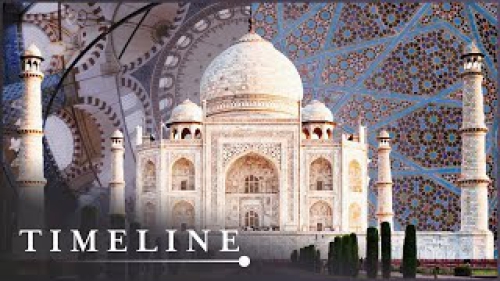

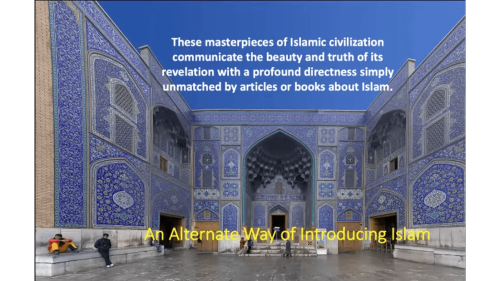

Through a genuine Islamic housing, Islam is being observed and presented in a way it ought to be observed and presented. Islamic housing is about beholding much of the Islamic ideology and creed at work. It is about witnessing a microcosm of Islamic society, civilization and culture. Islamic housing is about much of Islam taking up a manifest form. This accurate image of Islamic housing can go a long way towards correcting a great many misconceptions about Islam and Muslims within the ranks of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Islamic housing thus can become an excellent and effective means of da'wah Islamiyyah, that is to say, promoting the cause of Islam and inviting people to follow it.

*****

This article is an excerpt from the author's book "Islam and Housing"

Topics: Islamic Art And Architecture

Views: 1654

Related Suggestions