The Scientist Pope

Did you know that the Pope in the year 1000 was the leading mathematician and astronomer of his day? Did you also know that he was the first mathematician in the Christian West known to use Arabic numerals?

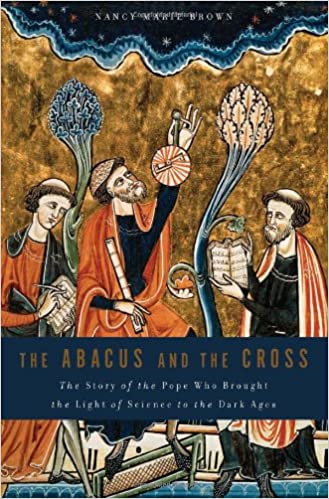

In this video, Nancy Marie Brown, author of The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages, explores a parallel universe, an alternate history of the Middle Ages, in which science was central to the lives of caliphs, bishops, kings, and even popes.

The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages, explores a parallel universe, an alternate history of the Middle Ages, in which science was central to the lives of caliphs, bishops, kings, and even popes.

The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages, explores a parallel universe, an alternate history of the Middle Ages, in which science was central to the lives of caliphs, bishops, kings, and even popes.

The Scientist Pope:

I was introduced to The Scientist Pope through an act of grace. Writing a book about an adventurous Viking woman, I made an imaginary pilgrimage to Rome just after the year 1000. Wondering which pope Gudrid the Far-Traveler may have met, I discovered Gerbert of Aurillac, who served as Pope Sylvester II from 999 to 1003.

I was astonished. Nothing in my years of reading about the Middle Ages had led me to suspect that the pope in the year 1000 was the leading mathematician and astronomer of his day.

Nor was his science just a sidelight. According to a chronicler who knew him, he rose from humble beginnings to the highest office in the Christian Church “on account of his scientific knowledge.”

I felt as if I had stumbled into a parallel universe, an alternate history of the Middle Ages. So I began writing another book, to share the story of The Scientist Pope.

A professor at a cathedral school in France for most of his career, Gerbert of Aurillac was the first Christian known to teach math using Arabic numerals.

He devised an abacus, or counting board, that mimics the algorithms we use today for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing. It has been called the first computer.

Gerbert made sighting tubes to observe the stars and constructed globes on which their positions were recorded relative to lines of celestial longitude and latitude.

He (or perhaps his best student) wrote a handbook on the astrolabe, an instrument for telling time and making measurements by the sun or stars. You could even use it to calculate the circumference of the earth, which Gerbert knew very well was not flat like a disc but round like an apple.

All of this science Gerbert learned as a youth living on the border of Islamic Spain—then an extraordinarily tolerant culture in which learning was prized.

In the caliph’s library in Cordoba were 40,000 books; Gerbert’s French monastery owned fewer than 400. Many of the caliph’s books came from Baghdad, known for its House of Wisdom, where for 200 years works of mathematics, astronomy, physics, and medicine had been translated from Greek and Persian and Hindu and further developed by Islamic scholars.

In the world Gerbert knew, Arabic was the language of science. Much of what Gerbert taught at his cathedral school in France, for example, was derived from the works of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, a Persian scientist in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom.

In the early 800s, al-Khwarizmi wrote a book on what we call Arabic numerals: He named it “On Indian Calculation,” well aware that the symbols 1 to 9, and the place-value system that makes arithmetic easy, originally came from India.

Modern algebra comes from a second book by al-Khwarizmi: You can thank him for quadratic equations. Al-Khwarizmi’s own name gives us the word algorithm, without which no computer scientist could function.

His third book is a set of star tables, in which he uses trigonometry, spherical astronomy, and other advanced math to calculate the changing positions in the heavens of the planets, sun, and moon.

Finally, al-Khwarizmi wrote a treatise on the astrolabe, which was the most important scientific instrument until Galileo invented the telescope in the 17th century.

Al-Khwarizmi’s books quickly reached Islamic Spain—perhaps even before his death in about 850. There, during Gerbert’s lifetime, a hundred years later, Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra and his treatise on the astrolabe were among the science books translated from Arabic into Latin through the combined efforts of Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars.

Many of these scholars were churchmen, and some of them became Gerbert’s lifelong friends. One of these is Miro Bonfill, the Bishop of Girona. In one of Miro’s books, he writes, “What follows now has been translated by the wisest scholar among the Arabs, as he was instructing me.”

Topics: Al Khwarizmi, Al-Andalus, Arabic Numerals, Astronomy, History, House Of Wisdom (Bayt Al-Hikmah), Interfaith, Mathematics, Muslim Mathematicians, Muslim Scientists, Pope, Quran Values: Knowledge, Peace, Tolerance

Views: 1351

Related Suggestions