Pilgrimage of Spiritual Awakening

In addition to Islam's spiritual, political, economic and other aspects, the religion is a social phenomenon constructed and understood through the vision and faith of its followers. As social phenomena, Islam and the Muslim community have changed since Islam's inception, and travel - whether it be in the form of Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), hijra (migration from lands where the practice of Islam is hindered), ziyara (visits to exceptionally sacred spaces), or rihla (travel in search of knowledge) - has played an important role in bringing about these changes. These forms of travel signify, above all else, a departure from that which is familiar and an encounter with the unknown. Muslim travelers return from their journeys aware of and appreciative of diversity and difference.

Appreciation of difference has always been important, but it is increasingly so in today's atmosphere of globalization. In the Muslim community, there are almost endless competing notions of "Islam" vying for control with some advocating a black-and-white definition of faith, completely oblivious to diversity of culture and interpretation. Rejection of such absolutist strains requires some knowledge of the world's social complexity as well as a deep understanding of Islamic tradition and spirituality. As one of the five pillars of Islam and an obligatory form of Muslim travel, the Hajj can be a primary means of achieving both of these ends.

Significantly, the Hajj takes pilgrims to Mecca, a city closed to non-Muslims. Whereas this exclusivity has been criticized by some as antithetical to religious freedom and tolerance, it plays an important role in helping pilgrims reexamine their spiritual state free from external criticism-an important fact in the modern landscape, where Muslims are under scrutiny nearly everywhere in the world.

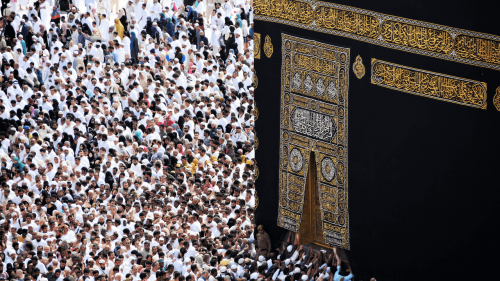

The Hajj pulls believers out of their environment and places them among new surroundings; it also gives them a different pace, marked by both calming and frenetic rituals. It beckons Muslims to go on a journey like no other, with the destination the K'aba - the center of the Islamic world, the earth and the cosmos. In journeying to this center, pilgrims delve into their inner selves. The world, community and self are united in a mutual quest; the Hajj is a journey to the heart of Islam.

The pilgrimage rites consist of the first tawaf, or circumambulation, around the K'aba, s'ai (to run, move quickly) between al-Safa and al-Marwa hills, standing vigil on the plains of Mount Arafat, and then, after stopping at Muzdalifa to gather pebbles, performing ramy al-jamarat (a symbolic stoning of the devil) at Mina. After this, the pilgrims return to Mecca to perform the second tawaf (tawaf al-ziyarah) and then spend the night at Mina, performing ramy al-jamarat of the first two pillars the next day, and then of the third pillar the day after that. The Hajj concludes with the third and final tawaf,tawaf al-wad'a.

The hajj, then, consists largely of imaginative reenactments of several prominent religious events. The s'ai, which involves walking seven times quickly between the hills of al-Safa and al-Marwa, reenacts Hagar's panicked search for water before an angel revealed the zamzam spring to her. The vigil at Mount Arafat places pilgrims at the site where the Prophet Muhammad delivered his Farewell Sermon to the Muslims who had accompanied him during a Hajj he performed toward the end of his life. Muslims believe that this is also the spot where Adam and Eve reunited on earth. The contemplative moments spent by pilgrims at Mount Arafat link them to the Prophet and, further back, to the beginning of time.

Soon after, the pilgrims perform ramy al-jamarat at Mina, pelting with their collected pebbles the three pillars symbolizing the three points at which the devil tried unsuccessfully to persuade Prophet Abraham to not sacrifice his son Ishmael in defiance of God's command. After ramy al-jamarat, pilgrims sacrifice an animal, just as Abraham sacrificed a ram when God, having mercy on Abraham, ordered that the sacrificial object be a ram instead of Ishmael.

These reenactments suggest that, to truly understand the Hajj, pilgrims must replace technicality with imagination. Some may perform the rites mechanically, but the very nature of the rituals seeks to jostle the pilgrims out of their indifference and help them conceptualize a time and reality other than their own. The rites connect Muslims to a primordial monotheism and remind them of their covenant with their Lord: that they will worship and obey Him. The message is apparent - Islam is and always has been. At its core, it will not change. The primordial nature of Islam is further underscored by the tawaf - circular movement suggests continuity and eternity. Tawaf connects one to the angels making tawaf in heaven and the black vortex in outer space.

But to appreciate these connections, pilgrims must exercise their imagination and learn to use that faculty more generally. As Dale Eickelman and James Piscatori explain in Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination, "Faith is accepted and sustained through symbol and metaphor, the very stuff of imagination which not only enlarges adherents' perceptions but reorders them so that the validity and rationality of religious faith and practice seem only natural." Pilgrims are to contemplate on the inner meaning of the rites and, using their abilities to imagine and innovate, apply the significance of those rites beyond the Hajj to their everyday lives.

During the s'ai, for example, reliving Hagar's desperate search for water in a desert and finding God's mercy among desolate mountains helps one find solace in the desolate, often lonesome modern state of being. There is something very "real" about going through Hagar's actions, something that pierces through the disillusion we carry of our mighty individualism and shows us on Whom we truly rely. Pilgrims walk in Hagar's footsteps to try to relive her total "faith" moment - finding "belief" among ideology.

Abraham was similarly victorious, and when pilgrims stone the pillars symbolizing the devil, they are reminded about a faith so strong that nothing could deter it and for which no sacrifice was too big. Those who think beyond the ritual and imagine the possibilities can become aware of the devil's interference in their own lives so that they may wage a spiritual battle against him similar to Abraham's. As Imam al-Ghazali explained in the Ihya' 'Ulum Al-Din, or Revival of the Religious Sciences, "As to the throwing of the pebbles, it is an expression of the thrower's intention to obey Allah's commandment, and a demonstration of his humility and servitude to Him. It signifies compliance with Divine commandment without any trace therein of any selfish pleasure, sensuous or intellectual."

Beyond the spiritual, there are social ramifications to embracing the imaginative as a way of looking at the world. Religious imagination is a powerful tool, one that can produce positive results. Although, as Michael Sells explains, there are seven forms of religious imagination that serve as the source of ideology and produce conflict, "monotheistic intolerance, purity of women, holy war, the idea of sacrifice, the claiming of sacred spaces including Jerusalem, the expectation of the Messiah, and perceptions of heaven". The Hajj suggests alternative, more productive forms.

For example, as Ebrahim Moosa notes in Pilgrims at Heart: "After paying homage to the two women Eve and Hagar in the rites of pilgrimage, how can some Muslims still violate the rights and dignity of women in the name of Islam? Is this not a contradiction?" Indeed, God's commentary on women's dignity is nestled within the Hajj rituals honoring Eve and Hagar.

The Hajj as a whole is a reenactment of Adam and Eve's wandering and reunion on earth after exile from heaven. Similarly, pilgrims, pulled away from all that is familiar, move from city to city, experiencing dislocation like exiles. Moreover, Eve's role as the mother of mankind is celebrated, silently, solemnly, meaningfully, when the pilgrims gather at Mount Arafat. She reminds all pilgrims of their common origin, irrespective of social divisions. Hagar and her faith are also celebrated, as her plight is the source of the s'ai. She is the vehicle chosen by God to undergo a religious test that will create a model for generations to come. As Hibba Abugideiri, Hagar was entrusted by God to do more than give birth to Ishmael. She was "a God-appointed messenger" whose struggles resulted in the birth of the Muslim civilization.

Islamic tradition has ascribed two possible reasons for why she was named Hagar. One is that she was a female migrant (muhajira); the other is that she was inclined "to distance herself from evil" (hajara). She, like Abraham, is a symbol of God-consciousness - a rarity in their pagan society. It is no accident that her plight is preserved in the Hajj, the function of which is to increase awareness of God. Consider the following dialogue between her and Abraham when he was about to leave her and Ishmael in the desert by themselves:

"Oh Abraham, where are you going, leaving us here without any people or sustenance?" He gave no reply. When she asked again and found he would not reply, she asked, "Is this ordained by God?" After Abraham replied yes, Hagar faithfully answered, "God will not let us die then."

Hagar stands for not just the respect due to women, but also for the dignity with which Muslims should treat the poor and underprivileged in society. No matter that she was an Egyptian slave, she had proven herself "worthy of divine instruction". Race, gender and class are man-made divisions; for God, dignity and worth are not dependent on such arbitrary categorizations. If pilgrims truly reflect on this matter, then imagination coupled with emotion can motivate the hajji (a person who has completed the Hajj) to look beyond the classifications and see all people as God's people.

Obliteration of class differences is further underscored by the ihram, a ceremonial outfit that for men consists of several unstitched white cloths. To further effectuate this end, Islamic tradition recommends that "one should have a ragged, dusty, untidy appearance, with uncombed hair, without much external ornament or any inclination to pomp and show. For otherwise, one might be inscribed among the proud and haughty who live in luxury, rather than among the weak, poor and pure in heart."

The simplicity and uniformity of the ihram overcome differences insofar as such differences are reflected in one's clothes. Ultimately, the Hajj erases superficial differences while celebrating the more meaningful ones. It brings the world to the pilgrims, many of whom have never before been outside their own countries, and educates them about peoples and cultures previously unknown to them.

During the Hajj, all pilgrims stand united in a single act of worship, equal before God and with equal access to Him. An open mind can grasp the true magnitude of this occurrence and use it to break down even the most deep-seated prejudices and fears. Consider Malcolm X's reflection upon seeing the diversity of the Hajj:

"On this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to rearrange much of my thought patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This was not too difficult for me. Despite my firm convictions, I have been always a man who tries to face facts, and to accept the reality of life as new experience and new knowledge unfolds it. I have always kept an open mind, which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth."

Importantly, the Hajj experience must extend the message of equality beyond the Muslim community. Humanity is diverse but united. Even among Muslims, the Hajj may fortify Umma-consciousness, but it simultaneously reflects the variants within the larger, unified community; though Islam is one, it is also richly heterogeneous.

The Hajj is a celebration of multiplicity - multiplicity of cultures, lifestyles, views and interpretations. Modernists, traditionalists, liberals and conservatives all meet and see how the others live and think. Imagination coupled with an appreciation for such multiplicity can awaken the pilgrims to "constructive possibilities" and serve as a potent tool against repression, absolutism and the terrorism.

Asma T. Uddin is Associate Editor of Islamica Magazine, a freelance writer and an attorney at the international law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP

Topics: Hajj, Hajra (Hagar), Makkah (Mecca), Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) Values: Spirituality

Views: 17378

Related Suggestions

You talk about the author of the article and about Hamza Yusuf, well, what have you done but criticize people.

And just like Hamza Yusuf would insert his own thoughts or comment in the same paragraph as a verse from Qur'an or Hadith, you do the same.

Hajar did not say, "God will not let us die then."

Hajar, as any Muslim will know, that to die is to return to Allah.

Thank you.