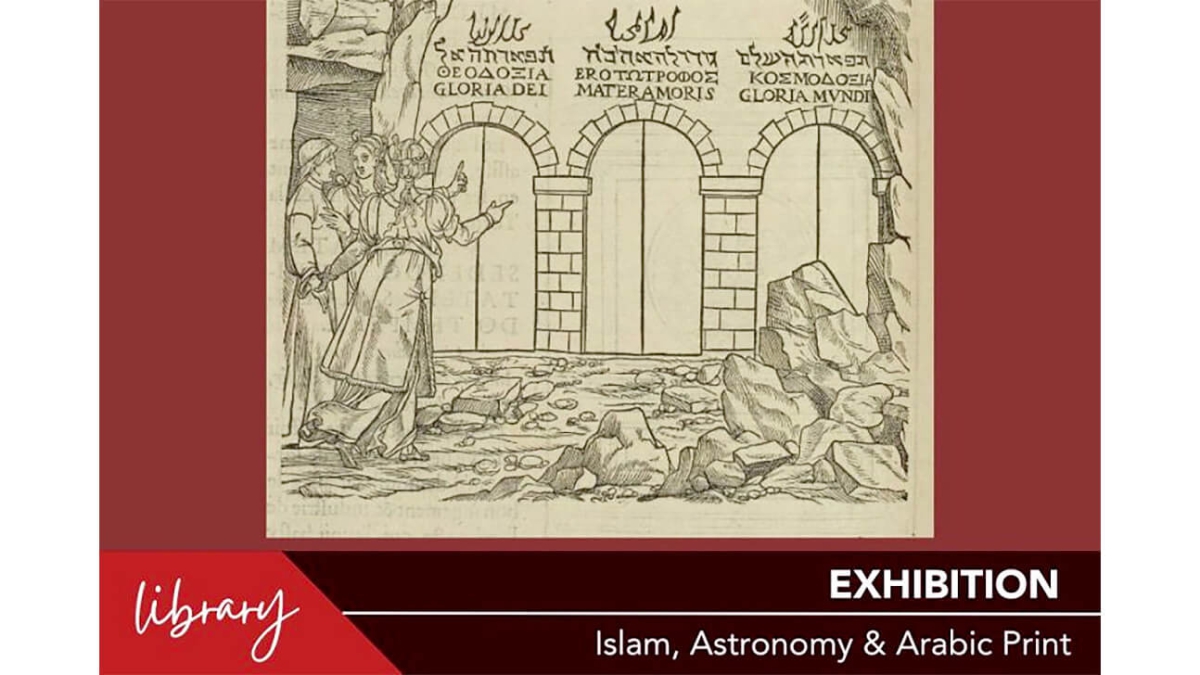

Islam, Astronomy & Arabic Print Exhibition at Middle Temple Library

This article gives a brief overview of the new exhibition at Middle Temple Library, ‘Islam, Astronomy & Arabic Print’. The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call its members to the Bar, which was established in the 16th century. For this reason, the library archives contain valuable historical manuscripts from the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods. The idea of this exhibition was to display exhibits from the special collections, which include early printed books containing Arabic script, European translations of Qurans from the Renaissance and Islamic astronomical manuscripts. The exhibition starts by looking at the early printed books.

Middle Temple Library has several early printed books containing Arabic script ranging from legal books to fiction. During the Renaissance, specialist Arabic printing houses were established in Oxford, London and various cities in Europe, to accommodate Arabic letters. The Arabic printing press was a response to the requirements of Orientalist scholarship which had developed significantly in 16th century Europe. Since the latest developments in fields of knowledge such as medicine, mathematics, science, astronomy and philosophy could only be acquired from the Muslim world, it became paramount for Europeans to learn Arabic and other Eastern languages, including Persian.

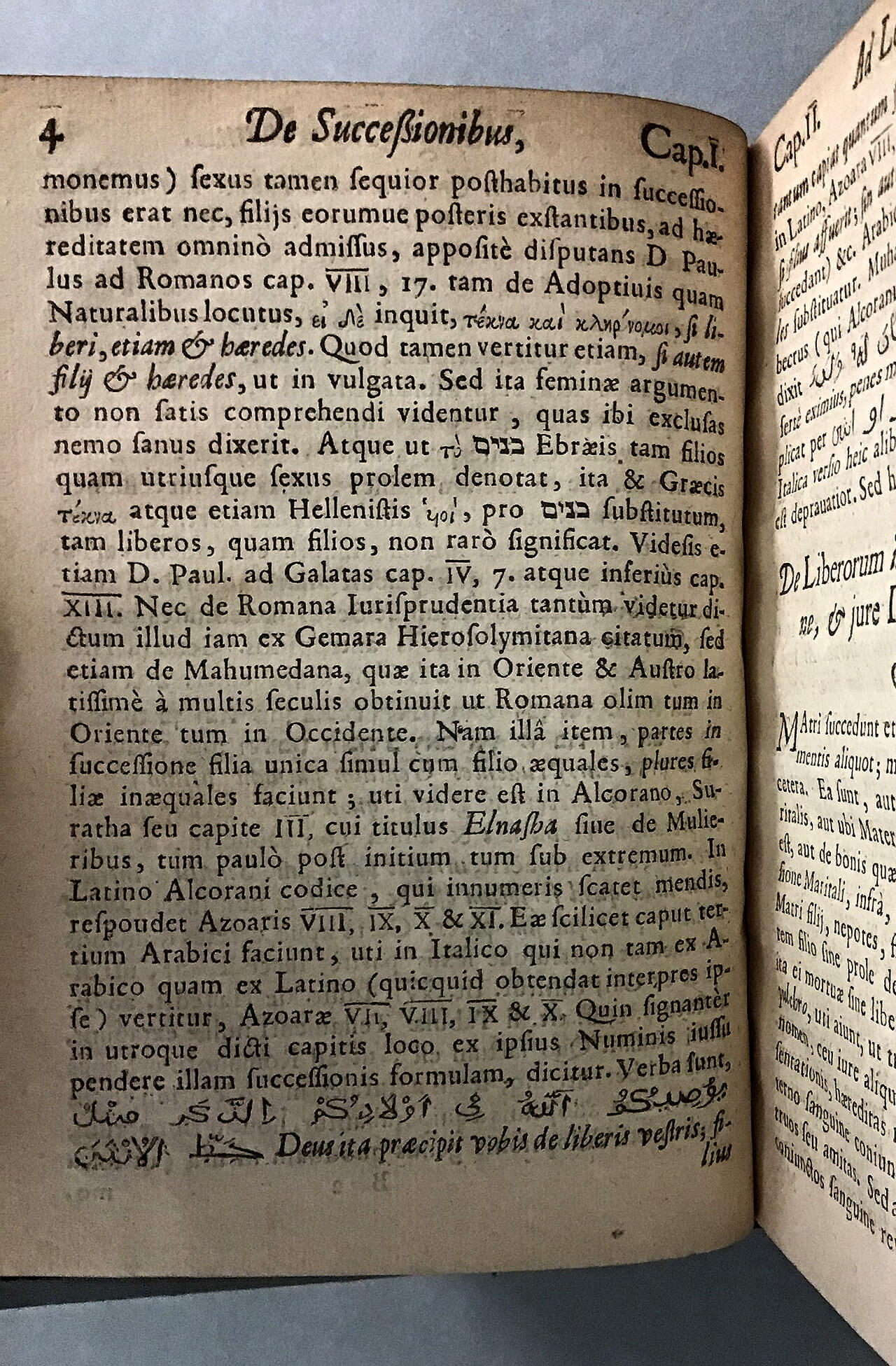

Many of Middle Temple’s early printed books were written by John Selden, a jurist, Orientalist scholar and member of Inner Temple. On display in a glass cabinet, is De successionibus in bona defuncti by John Selden published in 1631. His books show the difficulty of capturing Arabic characters in print. In the exhibition, are examples of Arabic script which show the progression of Arabic metal type and the improvement in Arabic script in English printing.

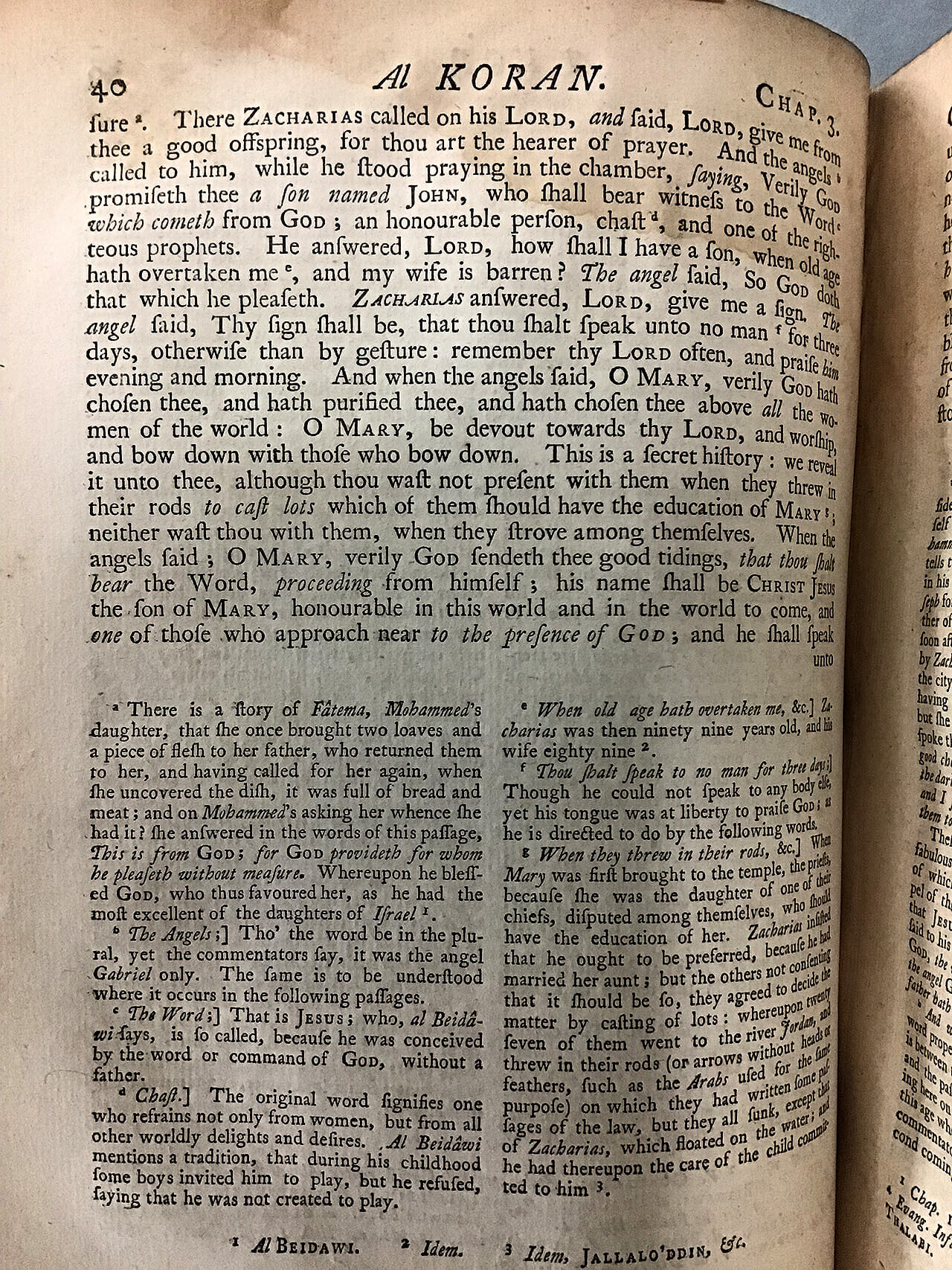

Alongside the early printed books, Europe also took an interest in translating the Quran. Initially, Qurans had been translated for political reasons to counter religious doctrine as a response to the Islamic empires which had been dominating the world from the 8th century up until the Renaissance. Some of the early translations contained biased and prejudiced stereotypes about Prophet Muhammad and Islam.

However, with the rise of Orientalist scholarship, there was a gradual change in approach to translating the Quran. In 1734, George Sale, a lawyer and member of Inner Temple, had the intention to create a translation of the Quran that was free from bias. To assist him in this endeavour, he consulted various authentic Ottoman sources to write a detailed commentary to accompany the verses. It was regarded as a fairly accurate version and was well-received by both non-Muslims and Muslims.

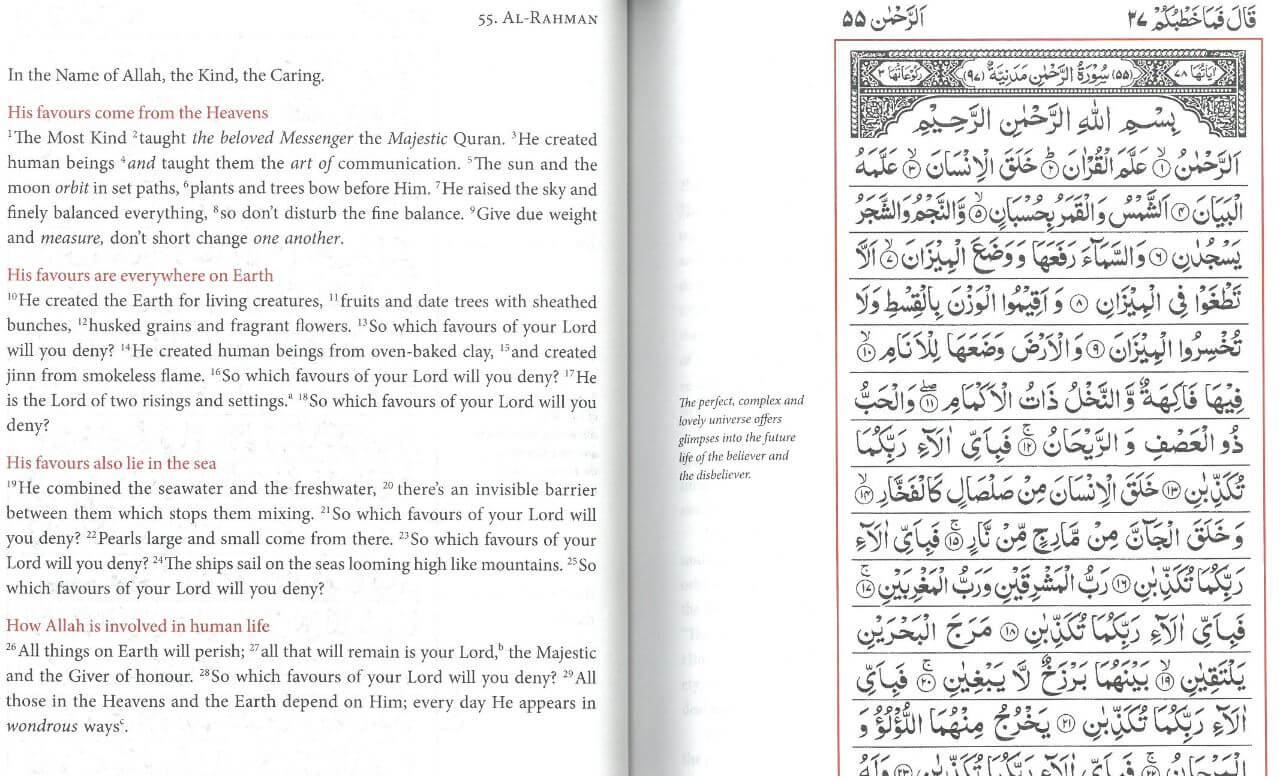

On display in the exhibition are various Quran verses relating to science and astronomy. As the early Muslim astronomers and scientists were polymaths, many of them also had a grounding in theology and the Islamic religious sciences, which include Tafsir (explanation of Quran), Hadith (sayings of Prophet Muhammad) and Islamic Law. As such, they would have been well versed in the numerous verses in the Quran that look at the movement and functions of celestial bodies and instruct the reader to investigate the universe and ponder their existence within it, to become firm in their belief in God.

The pursuit to understand the perfection of the design of the universe would also be a pursuit to understand the perfection of God, which is not dissimilar to the approach of the ancient Greek Astronomers and philosophers who used to contemplate the heavens. Observing and contemplating the universe can be an act of worship in Islam, if it leads to the contemplation of God. The field of Astronomy was seen as the height of scholarly pursuits as it was a way to truly know God.

The Quran places a lot of emphasis on being exact in measurements and calculations. As Muslims believe that the Quran is a source of knowledge and wisdom, this no doubt inspired the study of advanced mathematics and the creation of various tools to accurately measure the movement of celestial bodies, such as astrolabes and quadrants.

Islamic scholarship began in the 7th century when Prophet Muhammad started teaching the Islamic religious sciences to his followers. Over time, Islamic scholarship expanded to include various subjects such as medicine, mathematics, science, astronomy, philosophy, Arabic grammar, geography and the list goes on.

European scholars travelled to the Muslim world to gain knowledge on a range of subjects and also to acquire precious manuscripts. One of the earliest institutions that was attended by non-Muslims was the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco, founded in 859, by Fatima al-Fihri. Fatima al-Fihri was a visionary and after the death of her father, she used her inheritance to establish the institution to provide education to the masses. This is the world’s oldest university which still operates today and contains over 4,000 manuscripts. This university was one of many public institutions developed in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. Other institutions include observatories, schools, hospitals and the first public library.

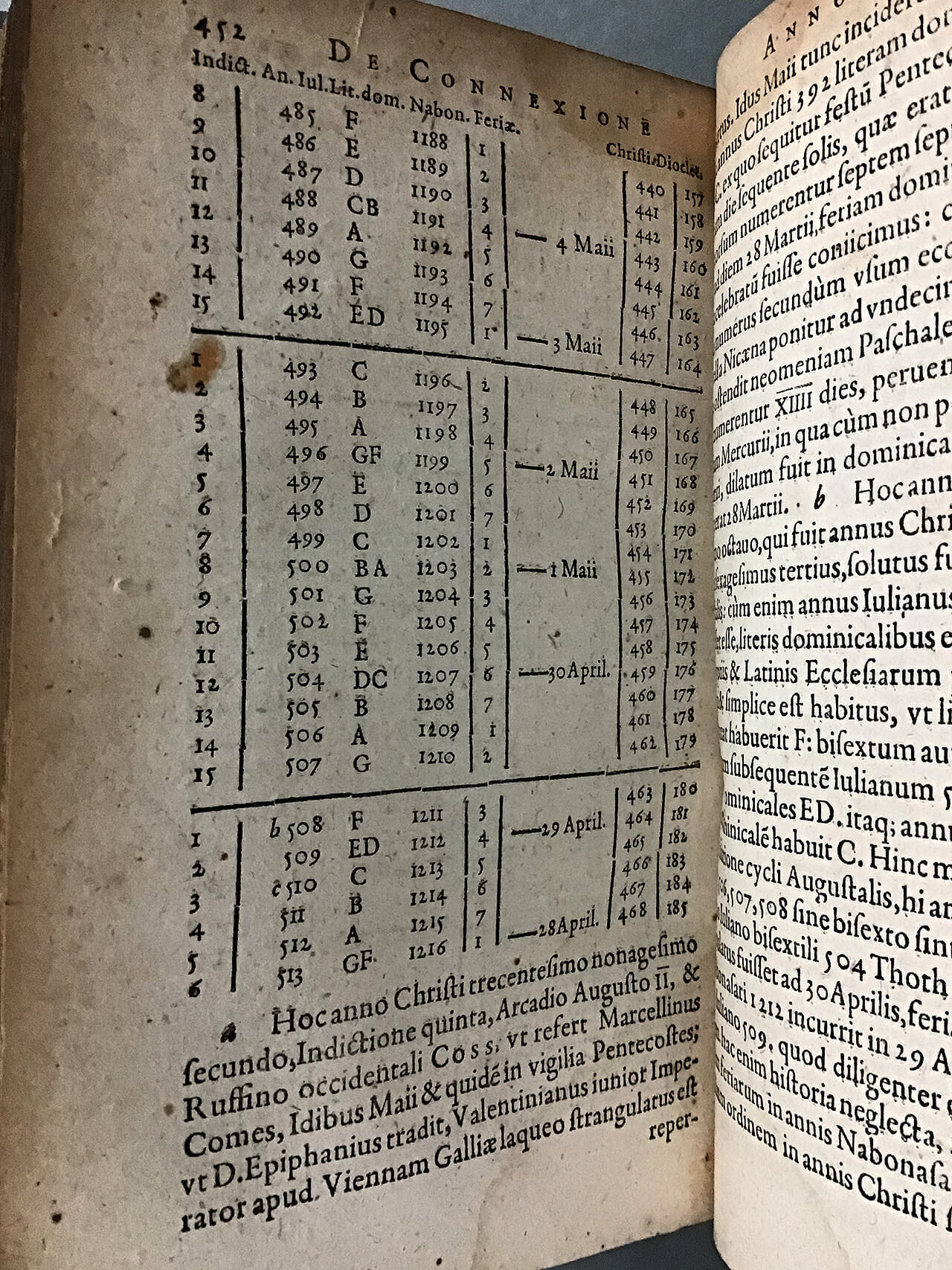

It would take a few hundred years before manuscripts from the Muslim world were translated into European languages. In the 9th century, Muhammad al-Farghani wrote Kitab fi al-Harakat al-Samawiya wa Jawami ilm al-Nujum (A Compendium of the Science of the Stars or Elements of Astronomy on Celestial Motions). It was first translated into Latin in the 12th century. It then underwent further translations into Latin and Hebrew. In 1590, Jacob Christmann, a German Orientalist, astronomer and expert in Arabic grammar wrote a third Latin translation which Middle Temple has a copy of. Al-Farghani was hugely influential on the astronomical works of European astronomers and his Compendium was used as a textbook in Europe. In his Compendium, Al-Farghani calculated the circumference of the Earth as well as the distances of planets from Earth. He also wrote several other works including a treatise on the astrolabe, an instrument used to find the direction of Mecca and calculate the prayer times according to the position of the sun.

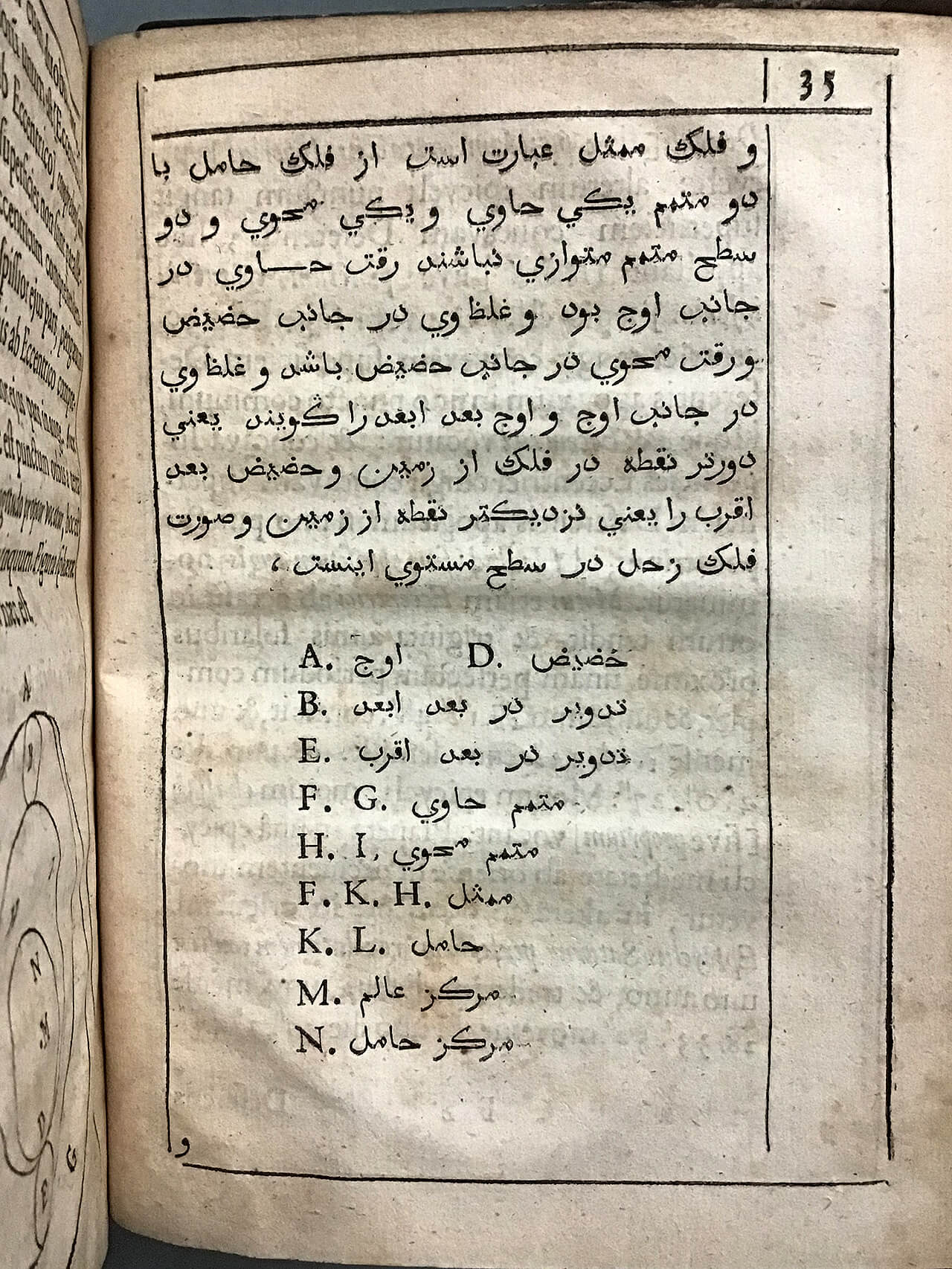

John Greaves, a Savilian professor of astronomy at the University of Oxford, was one of those European scholars who travelled to the Levant to acquire several Arabic, Persian and Greek manuscripts. His interests included weights and measures, astrolabes, geometry, astronomy and Arabic printing. In 1652 he translated Astronomica Quaedam ex Traditione Shah Cholgii Persae which was originally in Persian and attributed to Mahmud Shah Khulji, a 15th-century Sultan of Malwa, which is now central India. Astronomica Quaedam contains diagrams of the planets and the moon, geometrical definitions, and concepts relating to spherical astronomy, cosmography and cosmology.

In the exhibition, we look at Mariam al-Astrulabi and her work on astrolabes. We also look at the contributions of other Muslim astronomers, scientists and mathematicians in the field of astronomy. The contributions are so vast and rich that we could only focus on a few prominent figures in the exhibition, such as Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and Ibn al-Haytham. The contributions of Islamic scholars were clearly influenced by the teachings in the Quran and the emphasis in the Quran to pursue knowledge both religious and secular. Islamic scholarship still continues to this day and flourishes within Islamic educational institutions such as the renowned Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, which was established in the 10th century.

The impact of the works of these early scholars can still be felt today and can be seen in everyday life such as in the Arabic names of stars, and in advanced mathematical fields of trigonometry, geometry, arithmetic and algebra, which are key to the study of astronomical science. European scholars and Orientalists endeavoured to translate this wealth of knowledge, to the extent of creating an Arabic printing press in Europe, to assist in successfully transmitting knowledge to the West across several centuries. This undoubtedly resulted in the birth of Renaissance learning.

Middle Temple Library is not a public library, however, an online version of the exhibition can be found on the library’s webpage, which includes a promotional video about the Quran:

The exhibition will run until 11th September 2023 and can be viewed during the Library’s opening hours.

The exhibition can also be viewed online. Tip: click on the social media icon in the right-hand corner of the text cards to see the corresponding images.

Note of the Editor: This article has been written by Fariha Sikondari, co-curator of ‘Islam, Astronomy & Arabic Print’ at Middle Temple Library, which was co-curated with Jake Hearn. All Images are supplied by the author.

Source: Muslim Heritage