Masjid al-Haram Expansion: The Case of Shamiyyah

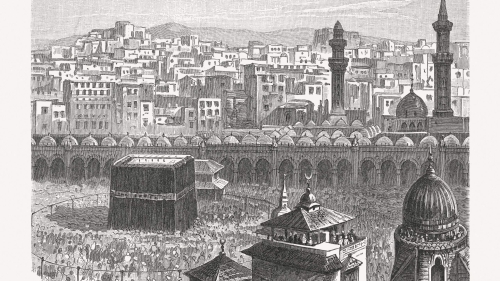

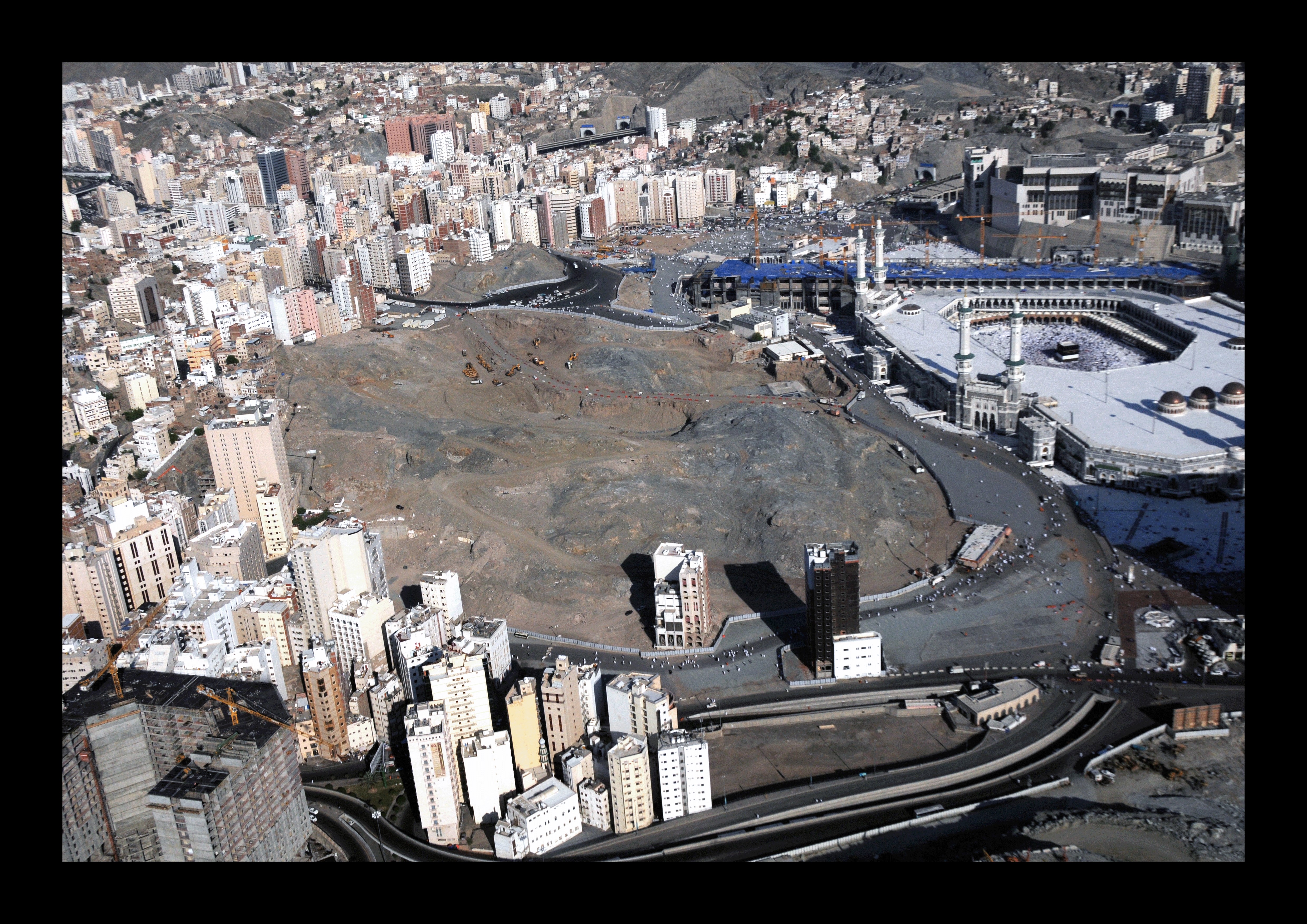

As part of the latest, grandest and most gargantuan expansion of al-Masjid al-Haram, entire neighborhoods on an unprecedented scale were pulled down to make way for the planned developments. One of the most affected areas was a Shamiyyah neighborhood. It lay north and slightly northwest of the Ka’bah (al-Masjid al-Haram), occupying significant segments of the Qu’ayqi’an range of hills.

According to Mu’jam Ma’alim al-Hijaz (Dictionary of the Landmarks of Hijaz), Shamiyyah was a residential area that overlooked the Marwah hillock from the Daylimi hill in the north, which in turn was part of the Qu’ayqi’an span of hills.

Admittedly, the Saudi government paid high prices for the land, so that the people who lived in the affected locales could move to newly developed suburbs on the outskirts of the city. As a result, the area that the city of Makkah covers expanded dramatically.

Whole sections of barren, stony wasteland have in the last few years become brand-new housing development and shopping districts. New shopping boulevards on the outskirts of the city contrast sharply with the narrow winding streets near al-Masjid al-Haram.

Shamiyyah was inhabited in some measure since the early days of Islam, some serious building activities having been associated with it for the first time possibly during the caliphate of Mu’awiyah b. Abi Sufyan (61 AH /680 CE), the first Umayyad Caliph.

According to some earliest historians of Makkah, such as al-Azraqi (219 AH /834 CE), the city’s residential neighborhoods were initially divided into two broad zones: the Upper and Lower zones. The Upper zone comprised the areas lying to the east, north and northwest of al-Masjid al-Haram, whereas the Lower zone consisted of the western and southern areas.

It was only in 1336 AH/ 1917 CE, after periods of significant increases in population, that the above method was rescinded and the city of Makkah was divided into twelve actual and geographically distinguishable neighborhoods or quarters, one of which was Shamiyyah. In 1348 AH/ 1929 CE, the total became thirteen, after another neighborhood had been added to the existing sum. Almost twenty years later, in 1368 AH/ 1948 CE, the number of neighborhoods climbed to seventeen.

Shamiyyah was a distinguished and prolific neighborhood, more than ever during the first and immediately ensuing periods of the Saudi era. On the word of a Saudi historian, Fawzi Sa’ati, in its heyday, Shamiyyah had twenty two schools, both primary and secondary, and some for male and some for female students. Of those, the school Madrasah Tahdir al-Bi’that – later King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Secondary School – was most outstanding. It was the first public secondary school in the whole of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Shamiyyah also had two printing houses, a journal “al-Irtiqa”, a Communal Literary Club, private and public Qur’anic recitation and memorization courses, twelve private and public libraries and bookshops, eighteen ribats (hospices or hostels), as well as many restaurants, coffee-shops, stores and markets that sold various types of goods virtually from all over the Muslim world. A long list of Shamiyyah businesses and businessmen, crafts and craftsmen, professions and professionals, have been provided. That affirmed that the place was a very important and self-contained locality. It bustled with social, educational and business life and activities. As such, it was frequently visited by high-level government officials.

On the eve of the evacuation of its citizens - which was followed by its destruction - the Shamiyyah neighborhood had about 1,240 buildings. Many of them were private houses and apartments, some of which were turned into part-time lodging for pilgrims during the pilgrimage season, while others functioned as full-fledged pilgrims’ accommodation.

Outside the pilgrimage season, the place had between 18,000 and 20,000 residents, whereas during it, it was packed with approximately 140,000 to 150,000 people. In the end, only 15% of the Shamiyyah permanent population was Saudis; the rest were either residing workers or the country’s non-Saudi residents. The local citizens’ migration was common.

Standing in the way of the main thrusts of the latest epic expansion of al-Masjid al-Haram were several old Makkah neighborhoods which heretofore adjoined al-Masjid al-Haram from the northern, northeastern and northwestern sides. They were: al-Mudda’a, al-Qararah, Harah al-Bab and, of course, Shamiyyah, neighborhoods.

It is widely held that Shamiyyah was a neighborhood that for so long was most representative of traditional Makkah (Saudi) especially domestic architecture, urbanism, culture and lifestyle. Such remained the case even though its reputation as such might have experienced a dip and greatly suffered both in the historical records of Makkah and in the sight of people. That was so on account of subsequent gradual administrative and operative negligence by certain governmental agencies and the residents alike.

The problem of Shamiyyah’s ultimate change of fortune could also be attributed, partly, to the unrelenting Saudi Holy Mosque restoration and expansion efforts over the years. The efforts run alongside and so, seriously affected a great many sectors of the area in question.

The widespread use of cars, with which those traditional neighborhoods with their narrow, winding and regularly steep streets were incompatible, was likewise a critical factor; as were some other well-nigh indispensable things, habits and expedients associated with modernization, progress and social transformation which the Saudi society was subjected to.

Expectedly, as a result, less new facilities and services were provided, while the old ones were not diligently attended to when their maintenance or upgrading was needed, causing the total wellbeing of the Shamiyyah neighborhood to gradually degenerate in the process. Scores of buildings in some parts were so poorly planned and built that they quickly deteriorated into virtual slums.

In its final phases of existence, to an insightful observer the place came to feel and look as though quite some time ago it had been sentenced to a civic death, or to a complete urban annihilation, and was just good-naturedly waiting for the execution of the sentence.

Those developments, especially during the latter phases of Shamiyyah’s existence, led to an exodus of many indigenous Saudi inhabitants, giving thus way to more businesses and traders, general workers and non-Saudi residents, in addition to a swelling number of visitors and pilgrims, to move in and, while congesting it, apply yet more severe strains on the place’s limited amenities and services.

This upsetting state of affairs could not solve anything; nor could it genuinely help anybody in a long term. Quite the opposite, it only underscored, perpetuated and nourished the causes that originally conceived and gave rise to it.

The above-inferences were derived from the available evidence and data featured in many old and new pictures, documents, videos and interviews. Moreover, the researcher himself visited quite a few times Shamiyyah and some of its adjacent neighborhoods prior to their destruction, and even resided there as a pilgrim on a couple of occasions.

Shamiyyah was the last of its kind in Makkah. Nonetheless, it was destroyed swiftly without officially and systematically documenting it, let alone considering the preserving of any aspect or dimension thereof.

Lessons learnt

The way Shamiyyah has been looked upon and dealt with intellectually, culturally and even spiritually - both by the authorities and ordinary populace - shows that Muslims in general are yet to formulate adequate responses to the rapid disintegrations and regressions which have been plaguing Islamic homogeneous cultures and civilization ever since the Muslim world was thrust into the uncharted terrains of colonization, westernization and modernity.

As integral segments of Islamic culture and civilization, yet standing in the forefront, Islamic art and architecture were affected perhaps most in the process. A great many unprecedented dilemmas and challenges were thrown up, which the Muslim artistic and innovative mind and spirit, unfortunately, are yet to fully come to terms with, let alone prevail over.

The destroyed architectural legacy of the Shamiyyah neighborhood, without it being allowed - never mind officially directed and coordinated - to be properly documented and studied, lays bare the truth that not only in Saudi Arabia, but also across the Muslim world at large, a huge gulf between people and art and architecture exists. It also demonstrates the powerful presence of intellectual and psychological conflicts between modern buildings and modern architectural styles and schools of thought, on the one hand, and rich Islamic history, culture, value system and traditional architectural styles, schools of thought and identity, on the other, and how rife they are.

The case of Shamiyyah likewise teaches that Islamic architecture needs to conceptualize and unambiguously demonstrate in practice a sense of continuity between old and new. No conceptual or real break or discontinuity is to be fostered, marking out different physical and metaphysical divides, understandings and outlooks, as well as worlds of concepts and solutions.

Islamic traditional architecture must be regarded as a central part of Islamic cultural heritage and identity. It is also to be seen as signifying an invaluable Islamic historical record which speaks volumes about how people understood and handled both the distant and recent past challenges. It thus should serve as a source of inspiration, enlightenment and guidance for the present as well as the future.

Inasmuch as Islamic traditional architecture is integral to Islamic culture and history, obliterating it would mean obliterating a part of Islamic culture, history and identity. To deliberately pour scorn on and undermine it would mean pouring scorn on and undermining a part of Islamic culture, history and identity, depriving thus people of precious assets and points of reference in their future community and civilization building undertakings.

Moreover, preserving and promoting in appropriate forms the spirit of Islamic traditional architecture would mean promoting respect for those who came earlier and created such an architectural heritage, and for those who will come later and be enabled thereby to witness and experience it themselves. It also means self-respect for the present-day generation on account of the following principle relating to civilization and society-building: in order for one to know and diagnose one’s present state, one must know his past; and for one to be able to chart his future course, one must know both his past and present conditions.

Without doubt, this applies as much to the fates of societies as to anything else, whose framework and unmistaken physical language is architecture. The disposition of a present condition in a society owes much to the past conditions that preceded it. Likewise, the disposition of future conditions will always owe much both to the present and past ones and how people attended to them.

People who are ignorant about, and indifferent towards, their history and culture are people with a fake identity. They possess no real life orientation, mission and purpose, regularly wavering in some of the most consequential things in life. Their civilizational undertakings, at best, are one-dimensional, myopic and superficial, often serving not their own interests, but the interests of those parties and groups to the rhythm of whose political or economic currents they swing.

The purpose of preserving traditional architecture also encourages current governments to become more sincere and dedicated in their current and future-oriented architectural and general development programs and missions, for they can rest assured that their efforts and investments, too, will not easily become worthless, outmoded and abandoned. Governments will know that their very existence and development activities will become part of a continuous and sustainable way of life and built environment traditions, rather than being singular, disjointed and short-lived phenomena.

The whole issue, in fact, is about pioneering and sustaining a built environment culture. It is about investing in the past, so to speak, in order to secure at once the present and the future. It is about taking care of the past in order to be taken care of by the present and especially the future.

Governments, therefore, have a chance to contribute significantly to the prospect of placing their own destinies -- in terms of boosting and safeguarding their legacies -- in their own hands, rather than becoming the victim of their own policies and misdeeds. That is owing to a principle that whatever goes around comes around, which means that actions, whether good or bad, will often have consequences for their executor(s).

Similarly, architectural preservation boosts the morale and self-esteem of ordinary citizens. It encourages their useful involvement in available projects and schemes. It gives them a sense of gratification as a result of their fulfilling of their duties and responsibilities towards enlightening and safeguarding the past, recognizing and orienting the present, and towards inspiring and charting their community’s future. Indeed, this is one of the most effective modi operandi for bringing and gluing people together. It could yet represent the core, as well as the unifying factor, of the exigent processes of public participation in architecture.

Indeed, Islam intrinsically has nothing against, or in support of, either tradition or modernity. So dynamic, thorough and all-inclusive is its message that it transcends the boundaries of what people in some relative contexts call tradition and modernity. Muslims who are bidden to epitomize the Islamic message in their words, thoughts and civilizational endeavors are expected to do the same, treating the tradition-versus-modernity dialectic in a different light and from a higher vantage point.

Thus, Muslims need not have any undue aversion to Islamic tradition because Islam was never a cause of any darkness or ignorance chapters in Muslim history. There were no dark ages in Islamic civilization. Such a thing would be an anomaly in a religion of ultimate light, truth and guidance for humankind as Islam is.

On the contrary, Islam was the root-cause of all goodness that originated in Islamic civilization and from which not only Muslims, but also non-Muslims, benefitted. It was only certain Muslims’ recurring misconduct that time after time held up the progression of Islamic civilization, ultimately causing it to come to a standstill. The problems thus were never Islam’s, but rather Muslims’. The same holds true for the latest conundrum with regard to the notions of tradition and modernity and what relationship ought to exist between them.

In the same vein, Muslims need not have any unwarranted or worship-like reverence for the modernity crusade spearheaded mainly by Western thought and values because, in essence, conceptually and epistemologically it was so conceived as to correspond to the immediate Western needs created by the Western Middle Ages or Medieval period. It was only later that by means of colonization and westernization drives, modernity came to be perceived and witnessed as a global phenomenon.

While its outward manifestations and operations seem customarily innocent and universally appealing, it is the inner philosophical dimensions of modernity, as well as the former’s everyday application entailing a myriad of ethical quandaries - which are often deceptively wrapped up in the wrap of supposed universal values drawn from such spheres of human value as encompass aesthetic preference, social order and overall human traits and endeavor - that prove the biggest impediment to unconditionally recognizing and espousing modernity. Muslim spiritual and intellectual awareness thus ought always to be of such a high level and quality that knowing how far to go, where to stop and what to take, or contribute, and what not, when engaging with various constituents of modernity, should be a comfortably manageable proposition.

What is Islamic architecture?

It is generally said that since architecture is indispensable to life and to man’s fulfillment of his vicegerency mission on earth, it occupies a remarkable place in Islam. It is a collective obligation. However, notwithstanding its significance, Islamic architecture is not an end in itself; it is a means by which another end, embodied in a set of cosmic goals, is to be achieved.

Thus, when using and judging an architectural expression, our interactive experiences with it must take into consideration not only what can be seen and felt by the five senses, but also an architecture’s intelligent and spiritual sides which are discernible only by a sixth sense. Architecture is not only to be looked at; it is also -- and that is more important -- to be experienced, felt and emotionally attached to.

Islamic architecture is thus broadly defined as a type of architecture whose functions and, to a lesser extent, form are inspired primarily by Islam. Islamic architecture is a framework for the implementation of Islam. As such, it facilitates, fosters and stimulates the ‘ibadah (worship) activities of Muslims, which, in turn, account for every moment of their earthly lives. Islamic architecture, it follows, can come into existence only under the aegis of the Islamic perceptions of God, man, nature, life, civilization and the Hereafter.

Accordingly, authentic Islamic architecture would be the facilities and, at the same time, a physical locus of the implementation of the Islamic message. Practically, Islamic architecture represents the religion of Islam that has been translated into reality at the hands of Muslims. It also represents the identity of Islamic culture and civilization where the notions of tradition and modernity are relative conceptions.

There is thus a strong relationship between genuine Islamic architecture and a society where it is conceived, produced and utilized. This is so because Islamic architecture signifies a long process where all the phases and aspects are equally important. The Islamic architecture process starts with having a proper understanding and vision which leads to making a right intention. It continues with the planning, designing and building stages, and ends with attaining the net results and how people make use of and benefit from them. Islamic architecture is a fine blend of all these factors which are interwoven with the treads of the ideology, traditions and values of Islam. Similarly, integral to the architectural processes are also local customs, traditions, geography and other numerous micro socio-economic considerations.

It is an endless debate whether and how much traditional neighborhoods with their traditional landmarks should give way to the colossal al-Masjid al-Haram development and expansion programs.

(The article is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book titled “Appreciating the Architecture of Shamiyyah”)

Topics: Islamic Art And Architecture, Islamic Culture And Civilization, Makkah (Mecca), Masjid Al Haram

Views: 3462

Related Suggestions