The Missing Link

“It was during the ten years of ‘Umar’s caliphate that the most important conquests of the Arabs occurred,” says Michael Hart in his book, The 100. “Caliph Umar’s reign saw the largest expansion in the history of Islam. To sustain this expansion he embarked upon one of the most innovative administrative reforms the world had yet seen. Political, economic, and social reforms which he instituted, to run the affairs of the state, became the model for efficient public administration. In a very short time he transformed the primitive and essentially local administrative structure into the most modern and global one of its time. People enjoyed basic human rights and freedoms during his rule, essentially unheard of at the time. If an old woman could question and criticize Caliph Umar in public without fear of retribution, then there could be no doubt about the freedom of expression prevailing during his rule.”

Encyclopedia Britannica (in its concise edition) notes that Caliph Umar’s mandates, “affected taxation, social welfare, and the empire's entire financial and administrative fabric” and that “he was noted for his justice, social ideals, and candor.”

Among `Umar’s most significant developments (mentioned in Abu Hilal al-`Askari’s Kitab al-Awa’il and Tabari’s history) are:

- Establishment of Bayt al-mâl or The Department of the Treasury

- Establishment of the judicial branch of the government, i.e., courts of justice

- Establishment of the Hegira calendar

- Organization of War Department

- Putting army reserves on payroll

- Establishment of the Land Revenue Department

- Survey and assessment of lands

- Establishment of a Census Department

- Establishment of provinces and districts (within each province)

- Establishment of taxation and customs departments

- Organization of the Police Department

- Establishment of military barracks at strategic points

- Establishment of rest houses on the way from Mecca to Medina for the comfort of travelers

- Establishment of a welfare allowance for children.

- Provision for the care and bringing up of foundlings.

- Declaration of the end of slavery (whether Muslim or non-Muslim).

- Stipends for the poor among the Jews and the Christians.

- Establishment of a Department of Public Education.

- Development of a system of canals and dams.

- Development of new cities and roads.

To efficiently run the affairs of these various departments Caliph ‘Umar established (what in modern times is known as) a government secretariat. Every government department had an office within this secretariat where separate registers were kept to deal with matters of the state. All official business of the state was documented in writing. Written memos were routinely issued by the Caliph to his government officials (including provincial governors). Treaties and agreements with other states were concluded and their texts kept on record within these offices.

But here is a point worthy of special note.

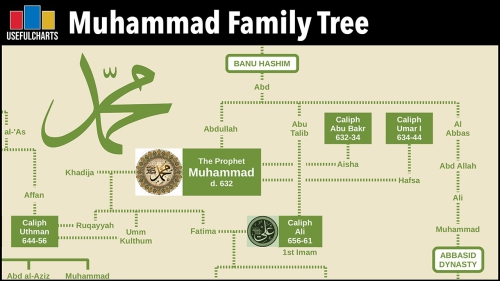

The Islamic state was established during the Prophet’s time. This region expanded during the period of Caliph Abu Bakr and reached to about two and half million square miles during Caliph Umar’s period. During this entire period (and even during Caliph Usman’s period) Medina was the capital of the Islamic state. The aforementioned secretariat, including all of its offices was in Medina.

Is it not surprising then that not a single original written record of that time exists today?

Medina, according to the historic record, has remained free from natural disasters. Neither earthquake, nor large fire is known to have occurred in Medina and there is no record of any calamity that could account for the destruction of so significant a collection of data.

Never has Medina come under the control of a crusading army or been subjected to an event that could explain why the records are missing. From the era of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) until the current day, Medina has remained under the continuous control of Muslims in a land well cared for and revered. Under these circumstances it is perplexing to figure how it came to be that no trace remains of such significant records. What has happened to all the documents? Who took them? Were they destroyed and if so, why?

Historians who have presented recensions of some of the records of those times have not mentioned where they saw the originals or what happened to them. There is no trace of the original records in our history books.

Early historians such as Ibn Hisham (d. 833c) and Imam Tabari (d. 923c) attempted to discern the more credible aspects of legend but lacked authentic documentation for reference. Hadith collectors, such as Imam Bukhari (d. 870 C), strove endlessly, (according to their own accounts), in search of original material for their books. Diligent researchers traveled to far off places and met hundreds and thousands of people. If there were written records available anywhere, it is reasonable to expect they would have found them. It is evident then and necessary to note that there were no original records to be found at that time, thus the early historians endeavored to compile their books on the basis of oral narrations. [Given this situation, it seems strange that we find in our history books detailed dialog, verbatim, between two soldiers in a battlefield, neither of whom survived!]

The original written documents that once existed were a precious historical treasure deeply relevant to the precedents established within early Islamic history. These valuable records should have been preserved as a sacred trust for the Muslim ummah. They would have proved valuable as a guide and blue print for the establishment and management of a true Islamic state. They would also have served as a worthy deterrent to anyone who tried to change the basic nature of Islam.

The inexplicable loss of records integral to early Islamic governance leaves questions that must be considered. Were there Muslims within the community who wanted to change Islam’s political and economic structure who may have felt that their desired alterations would not have been possible in the presence of documents that establish an Islamic precedent? Would Muslim kings have been able to rule abjectly in the name of Islam had records existed that established a set parameter? Was clemency in Islamic governance as established by Caliph Umar an inconvenient barrier to those who sought absolute power?

If a subsequent ruler or ‘ulema aspired to subjugate the masses, for example, by imposing excessive ritual upon the people, the presence of documentation specifying the natural order of the community, would have prevented deviations from the Prophet’s model. Without the original record, however, no evidence could be brought forward to bar whatever abuse or innovation a leader wished to impose upon the community. What led to this precarious development and what disaster, intrigue or tragedy could explain this mystery?

These are all questions worthy of our consideration. Yet, surprisingly, we find little to no research into what essentially amounts to a ‘missing link’ in our history. Although there are orientalists who look to this mystery with some interest, Muslims seem willing to sit content with their retellings rather than wanting to rise to seek out all relevant records and historic references to early Islam or to establish a renewed social ethic by returning to the heart of the revelation itself. It is discouraging to see that the majority of our historians and legalists are more intent on recycling the oral accounts that supplanted our history rather than searching to discover the authentic remnants meant to serve as our sacred trust.

Archeologists have found the Code of Hammurabi from the ruins of the ancient Babylon and Nineveh. They are busy discovering the ancient civilization of Egypt from the writings on the stones and walls in the tombs of the Pharaohs. Historians have even found the Dead Sea scrolls from the time before Christ. But, as noted before, not a single written document (related to the government of the Islamic state) has ever been found from the city of Medina when it served as the capital of Islam. [The few letters of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) that have come to our attention have come to us from areas outside of Medina under the control of non-Muslims.]

As far as we can determine, no historian has ever made an investigation into the whereabouts of the original written documents from the period of Caliph Umar. Is this investigation not worthy of our attention? We should keep in mind that Caliph Umar’s established parameters for running a government is generally recognized as a model for good governance even by non-Muslims. [Gandhi often cited Caliph Umar’s period of rule as a model of good governance.] Imagine the difference it would make to us had the original documents been preserved. It would aid us in defining the Islamic way of governance, in helping us resolve our endless sectarian arguments, in deciding what is (or is not) according to Shariah and in removing controversies surrounding secular versus conservative forms of Islamic government.

In considering the many benefits of the original documents that Caliph Umar left in our care, what would we say were he able to ask us what happened to this well-formulated and thoughtfully documented system of governance established as a just Islamic State? What could we possibly say?

Topics: History, Madinah (Medina), Umar Ibn Al Khattab

Views: 2357

Related Suggestions