From Al Azhar to Oak Park

She left for the Arab world, a young white American feminist. She soaked in the culture and religion like a sponge in the hand of the man she chose as her spiritual guide. Middle Eastern women also enlightened her about womanhood. Meanwhile, though partially blind, she nevertheless was able to drink in the wondrous sights of fabled Cairo, with streets right out of a centuries-old map she used as a guidebook, with breathtaking mosques for the praying. She hugged one of the first sheiks she ever met, moved into poor neighborhoods, ate oranges with the shopkeepers and mosque keepers, and met a family of closet Muslims in Spain. Now she's a Naqshbandiyya Sufi and a poet who "dresses for success." A divorcee, she is raising two Muslim children in Oak Park, Illinois.

I had studied Islam in order to develop a background for art history, and I fell in love with the whole romance of it. I was interested in the Sufi aspect but I didn't want to be a Muslim and do all that washing and praying and covering.

I had an introduction to the former dean of the faculty of law at Al Azhar, a wonderful man. I talked with him and he told me you can't be Sufi without being Muslim. I met the then grand sheik of Al Azhar. His secretary gave me private lessons on Islam. After four weeks I officially converted. I took the shahada by the grand sheik. Of course, the first thing that I did was hug and embrace him. He said, "Well, you know, now that you're Muslim, you really can't hug men anymore." I said, "Oh, okay."

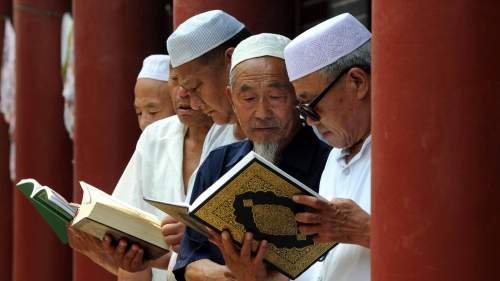

That was 1978, and it was unusual to find a foreign woman who was interested in Islam and had some knowledge about it. I was still actively seeking a Sufi sheik. I went to Damascus, and I met my sheik. When I met him, I was the first foreign follower to come to Damascus. He now has about 10,000 followers. They're Europeans-British, Germans, Swiss, Italian, and he has a big following in Malaysia and Sri Lanka. His original following, which he still has, are Turks and Arabs.

I had gone to the tomb of Ibn ' Arabi.And up the mountain from that tomb is where the sheik lives. Sheik Nazim al-Haqqani lives very simply. I was taken into his house into a reception room. He came out and sat down and drank a glass of water. It sounds silly, but it was clarity flowing into clarity. He smiled at me and said, "La illaha ill Allah," very softly and he didn't say much else for a while, and then he started to chat with me in English.

I stayed with his family there for a couple of weeks, and then he went to Lebanon, and I went on to England. During that couple of weeks, he didn't pressure me. He taught by example. I did a lot of extra prayers because he did it and it seemed to make him and his family happy. His wife was a sheika and gave a zikr (study session) for about two hundred women in Damascus. I was very impressed by his wife's learning. She had memorized a lot of the Qur'an. She spoke Arabic, Turkish, Russian. She knew the hadith (Sayings of the Prophet Muhammad)

When I look back on it it's amazing because there I was, this crazy foreigner, and I didn't know all of the Muslim customs and I would just barge into things. But there was this real acceptance and kindness. Occasionally there was a kind of amusement: Isn't this a funny little toy Muslim? Like a cat-dressed-up-in-doll-clothes kind of thing.

But there was this real sympathy too. Nobody beat me over the head with anything. They instructed me very softly. I told myself I had to bite the bullet and not be a women's libber any- more because I want to have all these mystical experiences. I have to do this thing and be oppressed. In Egypt the sexes do mix, but in Syria and other countries, you get thrown off with the women. Well, I would be outraged. And then it dawned on me: What am I saying? I'm saying they can't put me off with the women because nothing interesting happens with women; it's the men that the interesting stuff is happening with. Here I am really denigrating women! That didn't dawn on me and wouldn't have dawned on me had I not gone to an Islamic society and been mad and angry and thinking I've being thrown to the women.

Once I picked up a little Arabic, I really enjoyed going to the women's groups and being with the women. In pious Islamic society, there isn't this competition for men. It really makes a difference. I mean, they really are 'our sisters. If there's any competition, it's piety competition. It's a real nice kind of feeling.

Islam has really done that for me: it's really elevated my feeling that women are important and that being with them is important.

After I went back to Egypt my money ran out, and I became a teacher of English. From then on I never had any problems. I lived with really poor people, who didn't have sugar, salt, coffee, tea, and had never seen an antibiotic. They lived in materially deprived circumstances, had one outfit of clothes, but had the most elegant and lovely sense of manners and how to act. They had a kind of graciousness that you night think of in the fabled courts of Baghdad. This wonderful sense of awareness and intuitive feeling about people. That's a whole dimension to life that I had not realized existed.

I went on hajj in 1980 with a group of Egyptian men and women, and I realized that after that, no matter what, I could never not be Muslim.

I was the only American, so they kept thinking all the time when they looked at the passports that they had somehow gotten an American passport here by mistake. I lived and ate what they ate, so it wasn't a hardship for me. I was used to living very simply and eating very simply, and was used to the hot weather. A lot of people took me for being Turkish or Syrian. There's an area of southern Turkey and northern Syria where the women have light eyes. I have green eyes. So people thought I was from that area. When they found out I was from America, they were very friendly.

At the Ka'aba, there was this sense of incredible peace and unity-nonduality. At the Prophet's tomb, there was a sense of emotion and ecstasy and elation and love. I wept literally for hours and felt this overwhelming love and kindness emanating from the tomb. I still remember that. It was really something that I hadn't expected. There are two and a half million people there, and all of a sudden there's this wonderful, wonderful feeling. It seemed to be a love and a peace that didn't matter in the slightest whether you were American or Saudi or Persian or black or white. Clearly it was a blessing that was there for anyone who wished to partake of it.

In Egypt, I lived in a magical world. I was always praying in these exquisite mosques and I always lived in the old part of Cairo. It was sort of like an Arabian Nights quarter, where you could stand at a crossroads and look in all four directions and not see anything built after the thirteenth century; and where the artisans, like the weavers and the metal smiths and the cobblers, were all employing the same kinds of tools and the 'same methods that they would have seven hundred years ago.

I went to the American University and found a book that had a map of Cairo under the Fatimids.The Fatimids were like a Shi'a dynasty that ruled from 909 to 1171. That map showed the disposition of the craft guilds along the major streets of Cairo at that time. I found the streets still bearing the same names. I walked along them and, sure enough, in the spot that was marked charcoal makers, there were still charcoal makers. In the Spot marked coppersmiths, there were still coppersmiths.

In the spot marked tent makers, there were still people making canvas tents and carrying bags and feed bags. There was this extraordinary continuity of site use. And you know, Middle Eastern dress hasn't changed probably since the time of Ibrahim. It was like sort of a living museum, magically transported into the past. It was very romantic-an art historians dream. And it was really easy to forget that anything else existed. It was intoxicating. The map was in a book called Fatimid Cairo. There were photographs of still-extant buildings, and there was a map that had been made at the time that those buildings had been put up. The map showed what buildings were there and which were the ones that had been removed. There's one mosque that has a beautiful wooden railing that's been there since 1200. It's unimpaired because the climate is so dry.

I used to make every prayer in the mosque. Women, were readily admitted to the mosques; they were a real essential part of Egyptian life. Middle class women would come. Women selling oranges in shops were there. During Ramadan, everybody was in the streets. Women had access to everything. (That wasn't the case in Sudan. In Sudan, in 1981, I couldn't get into the mosques. And also in Kashmir, I was put in the women's room! Which obviously hadn't been opened in about fifteen years; everything was full of dust. The Custom there is that it is not suitable for women to come to the mosque. So the area that had been prepared when the mosque was built had never really been used, and you couldn't hear the imam, so you couldn't hear the congregational prayer. That would have upset me had I not bee in Egypt so long.)

There are all the big mosques that are written up in art books. But there are so many really exquisite little mosques in what we would call the slums. And most visitors don't really go and look at them. To a Muslim, the beauty of a mosque is not just its architectural splendor but also the feeling. You go in, you feel so comfortable. There is a blessing that comes where people have prayed over and Over for a thousand years. Mosques that have been turned into museums don't give you that feeling.

Very seldom did I see a mosque that I didn't like. My particular favorites were some jewels that were tucked away. Hardly anyone came to them except me and a few other people. Late Mamluk, 1350, and it hasn't been touched! And you'd come in and you'd pray.

When the mosques were built they were endowed. Shops were built around the base of the mosque, and the revenue from those shops continue to support the mosque. Those things are still going. It's really a good system. In the South of France, the churches have Romanesque capitals. They're very elaborate and have all these wonderful little bounding figures. They also have sort of twisted designs. In fact, those designs often say Bismillah- ar-Rahman-ar-Rahim. Perfect Arabic. I was astonished.

The Muslims were stopped in France, but before that the South of France was very Islamic, and whether those people were forced to convert to Christianity or whether they were artisans who were continuing a tradition of which they didn't know the meaning, I don't know. If you don't know Arabic, it just looks like an interesting arabesque. Design. But if you know Arabic, then oh my gosh, look what that says! And of course, in Spain that's allover, because the people were forced to: convert to Christianity and they continued their work.

When I was in Cordoba, I went to the Great Mosque, which was a tourist spot with this Christian church built in the middle of it. But it's just exquisite. It's a big mosque and it was a day when there weren't very many people in it. It came time to do the prayer, so I just did my prayer there in the mosque. I get up and there's this Spanish guy behind me. I thought, oh my God, what have I done! He comes up and says, Assalaamu alaikum." I say, "Walaikum salaam." He takes me to his house and he is one of the mosque keepers. He works for the tourist bureau. He and his family are crypto-Muslims. They've been Muslims since before 1492.

He has pictures of his grandparents wearing Muslim garb inside the house, turbans and things like that. He was so amazed to see someone praying in the mosque. Now, there are a couple of Sufi communities living there.

In Ramadan they would make extra prayers and things. They certainly weren't in a supportive environment. He said his family would have been tortured. "On the outside we're Christian and we went to church, but on the inside we always kept Islam." They kept the Qur'an in a venerated place, and they had read it, and they marked the passage of Ramadan in some way, for five hundred years.

He was really touched that somebody was praying there, right out in the open. But it's a mosque. It's prayer time, so pray, right? He said his family felt like they were guardians of Islam in Cordoba; they were the ones who kept the mosque clean and kept the doors locked. That was something their family had chosen to do, because it enabled them to have a more full experience of Islam, even though it had to be hidden.

As you remember, during the Inquisition, anybody who was even remotely suspicious was likely to be dismembered for the mercy of Christ. So it really wasn't safe, but they felt somehow in keeping up the mosque that they were doing a duty for Islam.

I thought it was nice, because it was an example of how Islam can be hidden in the heart and be kept up all of those years and kind of guarding the tradition and the mosque.

In order for a religion to convert lots of people it has to, to some extent, be cognizant of their native traditions. If it isn't, converting those people isn't going to be successful in the long run, and both Islam and Christianity have been able to absorb some animist elements from indigenous African people, and you see that in Sudan. There are still traditions of people throwing bones to predict the future.

And in Sudan, a woman is not marriageable unless she's had a clitoridectomy. It's just horrible. They have all kinds of infections. Every menstrual period is agony. It is not, however, an Islamic custom. The Christians also do that.

But the people are really solidly Muslim. You talk about fasting in 120- degree heat! Somebody died in Port Sudan when I was there in Ramadan.

The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 and finally abolished in 1834. During the first two centuries, the Inquisition in Spain resulted in the imprisonment, torture, execution, and exile of some 3 million Muslims and Jews.

The imam got up in the mosque and said, "No, no, no, this is not the intent. For heaven's sake, if you feel that bad, drink water. The intent of this is not to die." So people were literally willing to lay down their life in Ramadan to fast.

In Third World countries, you have lots of people and animals out in the street. America is set up like you're living inside this big machine. America was really hard to get used to.

I'm a great believer that the shape of things affects people and that there is a sacred shape to architecture. Mosques have a lot of empty space. There isn't a statue toward which you direct your prayer. There isn't an altar.

You're directing your prayer horizontally toward Mecca and vertically toward Allah. And into your own heart. There's this sense of positive space. The mosque is empty so that it can be filled with the spirit of God. There's an Islamic sensibility, whether it's the Taj Mahal or the Sultan Hasan mosque, and mosques are expressions of this.

I miss that, praying in my living room. I live very far from mosques. And the ones here are new. Al Azhar mosque is very old. It was built by the Fatimids. It had some plasterwork by one of the mihrabs, and they "beautified" it by removing all of that old plasterwork and putting up these sheets of marbleized plastic, so it looks sort of like the inside of a cheap bathroom. But they were so proud of it. They took all of that old crumbly plaster down, and put up this really neat stuff that you could just tack on and wash. It had these fake marble veins. It was like linoleum. It was really sad.

But that's my judgment. And I don't want to be guilty of intellectual colonialism, which is like going over and telling them what's good for them: You should like the old stuff instead of the new stuff. Liking old stuff is kind of a luxury of First World people who have new stuff and have the luxury to sentimentalize. They don't have to live with the difficulties and hardships of that old stuff. Old earthen pots may be beautiful, but carrying them on your head compresses your spine, so that a lot of the women in Sudan and Egypt have spines in bad shape. But if you carry big plastic jugs on your head, it doesn't do that to your spine. But I miss the beauty. And sure, I miss the congratulations of people patting me on the back and saying oh how wonderful it is that you became a Muslim. There was always some kind of reinforcement. Living here once again is sort of like what the Prophet said when he ' came back from a jihad-that he was returning from the lesser jihad to the greater one. The greater one being when we fight our egos and our vain desires.

I do believe that God is everywhere and that you can't live without the presence of God. I still feel the presence of God just as strongly in America t as I did in Cairo or Damascus or Delhi or wherever. But the problems that I have are accommodating the Muslim lifestyle, particularly dress, to the contemporary urban American environment. I ' think it's easier for immigrants to dress Islamically than it is for people 11 who are obviously American.

It's much harder for Americans to wear the kind of clothes that immigrant women wear, because people regard that as, well, part of their culture. That's natural for them. But for Americans it's immediately visible " that it's not part of traditional American life. These people are dressed as: Muslims. Well, Muslims are not Christians, so they've obviously rejected Christianity. And currently Muslims don't do very well in the world press. These are the people that are blowing up airplanes. You hear all of the negative things that terrorism brings in its wake.

It's been pointed out many times that it's much easier to be a Buddhist or a Hindu and dress like one in America than it is to be a Muslim. Because we never really had that much contact with Buddhists and Hindus, but because of the Crusades and the ebb and flow between Europe and the Middle East, there's a lot of antipathy toward Muslims. It's age- old.

Even with all the negativity, Islam is the fastest-growing religion in Europe and America. So I feel like it's the wave of the future. And I'm pleased to be part of it. My sheik emphasizes that it's very important to follow the shari'ah, because that's the way we submit our behavior to God. Assimilation in the Jewish sense of the word is really out of the question. But I think flexibility is possible. What I do is cover my hair with a hat often, rather than with a scarf. That way I don't feel like I attract undue attention.

Yesterday I saw a woman in Dunkin' Donuts. An American woman and her husband and she was fully veiled. I don't think she could have caused any more distraction. People couldn't have scrutinized her any more fully. It was as if she were wearing a bikini to come in to buy doughnuts.

For those sisters who can carry that, that's wonderful. My personal feeling is that if you're going to dress in a way that calls a lot of attention to yourself, you're defeating the purpose of hijab. So I dress in what I like to think of as an American Sunnah. It's what I call Muslim dress for success: suits-because I have baggy jackets and long skirts and hats and scarves.

I used to go to a shop and buy things, and the clerk was always so nice to me, and I would have my children with me. There were times when she looked like she was almost going to cry. I couldn't understand what was the matter. We talked about our lives. I told her I was divorced. She said, Oh, how sad." I said, "Well, yeah, but lots of people are divorced." Finally she said to me, "Have you thought about making provisions for your children? Just in case?" I said, "In case of what?" She didn't want to say. She's looking all around, and she finally says, "Are you in a cancer support group?"

I said, "No," and then I realized. Many women who have breast cancer have radiation therapy that makes their hair fallout, and they wear scarves. I know a couple of cancer sufferers who are Christian who look exactly like Muslims because they don't have any hair and they cover their heads with scarves.

I explained that I cover like this because I'm Muslim, and that's part of our religion; it's not because I have cancer. It's kind of comical yet sad. I try to wear scarves and leave a little hair sticking out to show that I do have hair.

Steven Barboza is an American Journalist who converted to Islam after discovering Malcolm X and his ideology. Barboza later learned that this early ideology that was held was not the true Islam and that through struggle Malcolm X became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

Topics: Al Azhar University, Women

Views: 7638

Related Suggestions

This article feels utterly genuine and spot on regarding all the religious and spiritual points that the author(s) touched on. I know because I lived in Cairo for a total of six years and "reverted" to Islam through sufism when I met the Sufi Naqshbandi group there. I also fell in love with every heart-stoppingly beautiful old mosque (minus the ones sadly plastered with "linoleum") in which I prayed or just visited, and they are indeed legion.

There is only a minor point with which I disagree. I feel that wearing Hijab and/or the "Muslim dress" can be easier for many converts/reverts who don't associate a lot of heavy emotional baggage with it, as some Muslim-born women do. The spirit can be all too willing, but I feel that, sadly, the burden of that baggage often weakens the hijab wearing-spine!

That said, I find the authors incredibly attuned to Islam and traditions in ways that many Muslim-born can only envy and could happily emulate. I find their sincerity and openness deeply touching and inspiring. Is that partly due to the Naqshbandi Sufi "Path with a Heart" touch? I think so. Few if any who meet Sultan al Awliyas Mawlana Sheikh Nazim Q, have the immense privilege of living with him and his family at Jabal Qasyun near Damascus, even for short while, would not be profoundly changed for the better, forever....

Thanks for publishing this article. A welcome relief from some of the ugly and misinformed sputterings against Islam of the hate-mongers out there. Wish they would read it with an open heart: maybe ot would would grow aat least one size bigger? Warm salams.

Ahadun Ahad