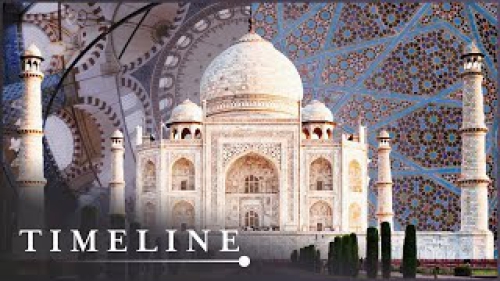

Islamic Architecture between Tradition and Modernity

“The best solution for Islamic architecture is to be traditional, but without just blindly imitating and repeating the past, and modern, albeit without rejecting tradition and constantly seeking to break with the past. Tradition and modernity in Islamic architecture must be at peace, rather than at loggerheads, with each other.” Traditional and modern architecture in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

In the light of our interpretation of tradition and modernity, Islamic architecture, in its capacity as a physical locus of the actualization of the Islamic message and a representation as well as a microcosm of the identity of Islamic culture and civilization, needs to be both traditional and modern. It needs to be traditional in the sense that it will be based on people’s perennial social, cultural and religious needs, will make full use of common regional forms and materials which certain communities were evolving and making recourse to for centuries, and will through its form and function exemplify and exude both Islamic undying principles and values and the local customs and practices in relation to a particular place and time. That is to say, Islamic architecture should reflect the environmental, cultural, technological, economic, social and historical context in which it has been planted.

Moreover, Islamic architecture, at the same time, ought to be modern as well, in the sense that it will use modern materials, techniques and systems, will use traditional materials and systems in new and creative ways which will be ingeniously integrated with the former, will adopt the principle of “form follows function” and in the process avoid extravagance, pomp, clutter and all the unnecessary factors and ingredients, will adopt the principle of “complexity in simplicity”, and will be maximum-efficiency disposed in connection with its structural, serviceable and functional purpose. That is to say, Islamic architectural design principles will be reconciled with rapid scientific and technological advancement and the modernization of Islamic societies. In other words, Muslim architects need to produce buildings that are recognizable of our own age but with an understanding and respect for religion, history, culture and context. If this will involve some challenges to public taste and convention, it may not be a bad thing. The trend should lead to a situation where the two polarities, if at times not fully patched up and unified in some new creative and original architectural design solutions, then new is to be distinguishable from traditional - albeit neither ostentatiously nor uncouthly - and traditional is to be treated with maximum care and integrity.

Moreover, traditional is not to be relegated and subjected to some substandard undertakings, therapies, technologies and economic as well as socio-political interests and concerns. Nor is it to be underestimated and neglected to the point where those involved in whatever capacities with it will become prone to developing an architectural inferiority complex. Such attempts towards reconciliation and amalgamation between modern and traditional in Islamic architecture, in spite of posing challenges to some public perceptions and predilections, will surely generate debates and even controversies that will ensure that professional scrutiny and public interest are alive and well. At any rate, so disappointing and worrying is the state of the contemporary architecture of Muslims that with the said reconciliatory and integrative architectural approach, in the end, everyone is set to win basically everything and lose virtually nothing.

Unquestionably, there is nothing wrong and everything right about using obvious and explicable Islamic traditions, which are fully charged with Islamic spirituality, in modern Islamic designs. Similarly, there is no good reason why being original is restricted to being non-traditional, why being creative means that nothing from the past can be borrowed, re-interpreted and re-applied, and lastly, why modern inventions have to look odd and unpredicted only. As Robert Adam, while speaking generally about tradition as the driving force of urban identity, observed that “traditional design can be original, it can be creative and it can take on new things – it can even invent new traditions. If only we could all understand this, we could have a public that understands us, we could add to our historic culture instead of fighting it.” (Tradition: the Driving Force of Urban Identity, inside “Context: New Buildings in Historic Context”, p. 37).

According to Garry Martin, Islamic architecture of the past was always in harmony with its people, their environment and their Creator. The great mosques of Cordoba, Edirne and Shah Jahan - for instance - each used local geometry, local materials and local building methods to express in their own ways the order, harmony and unity of Islamic architecture. But in the 20th century, the Islamic concepts of unity, harmony and continuity often are forgotten in the rush for industrial and modern development. Garry Martin then lists three directions contemporary Islamic architecture can take:

1. One approach is to completely ignore the past and produce Western-oriented architecture that ignores the Islamic spirit and undermines traditional culture.

2. The opposite approach involves a retreat, at least superficially, to the Islamic architectural past. This can result in hybrid buildings where traditional facades of arches and domes are grafted onto modern high-rises.

3. A third approach is to understand the essence of Islamic architecture and to allow modern building technology to be a tool in the expression of this essence. Architects working today can take advantage of opportunities that new materials and mass production techniques offer. They have an opportunity to explore and transform the possibilities of the machine age for the enrichment of architecture in the same way that craftsmen explored the nature of geometrical and arabesque patterns. The forms that would evolve from this approach would have a regional identity, a stylistic evolution, a modern appeal and a relevance to the eternal principles of Islam. (The Future of Islamic Architecture, http://www.islamicart.com/main/architecture/future.html, accessed on June 15, 2015).

It goes without saying, therefore, that the best solution for Islamic architecture is to be traditional, but without just blindly imitating and repeating the past, and modern, albeit without rejecting tradition and constantly seeking to break with the past. Tradition and modernity in Islamic architecture must be at peace, rather than at loggerheads, with each other. Their synthesis will serve as an inspiration and source of endless design opportunities and ideas. Only this way, undoubtedly, both tradition and modernity in Islamic architecture will be bound to triumph.

Otherwise, they both will dreadfully fall short, causing thereby a considerable irreversible damage to the future of Islamic architecture and, by extension, to Islamic civilization.

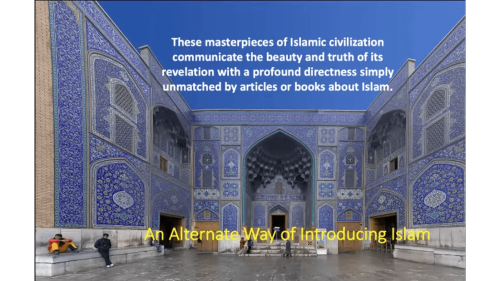

On the whole, therefore, genuine Islamic architecture is seen as a type of architecture whose functions and, to a lesser extent, form are inspired primarily by Islam. Islamic architecture is a framework for the implementation of Islam. As such, it facilitates, fosters and stimulates the ‘ibadah (worship) activities of Muslims, which, in turn, account for every moment of their earthly lives. When properly perceived and practiced unobstructed, the universal, fluid, multi-dimensional and value-loaded character of Islamic architecture always eventually comes to the fore in any given socio-economic, religious and cultural context.

Islamic architecture, accordingly, can come into existence only under the aegis of the Islamic perceptions of God, man, nature, life, civilization and the Hereafter. Thus, authentic Islamic architecture would be the facilities and, at the same time, a physical locus of the implementation of the Islamic message. Practically, Islamic architecture represents the religion of Islam that has been translated into reality at the hands of Muslims. It also represents the identity of Islamic culture and civilization where the notions of tradition and modernity are relative conceptions.

There is thus a strong relationship between genuine Islamic architecture and a society where it is conceived, produced and utilized. This is so because Islamic architecture signifies a long process where all the phases and aspects are equally important. The Islamic architecture process starts with having a proper understanding and vision which leads to making a right intention. It continues with the planning, designing and building stages, and ends with attaining the net results and how people make use of and benefit from them. Islamic architecture is a fine blend of all these factors which are interwoven with the treads of the belief system, teachings and values of Islam. Similarly, integral to the architectural processes are also local customs, traditions, geography and other numerous micro socio-economic considerations.

So, therefore, the multi-tiered realm of architecture, in general, is not to be viewed only through the lens of architecture as pure art, science and technology. Rather, it is to be expanded into the higher and more sophisticated realms of existence. Existence, on the other hand, is not to be distorted or narrowed down, so as to go well with the corporeal ingredients and dimensions of architecture only. The orb of architecture, it follows, is to become known as an ultimate spiritualized and “supernatural” orb, whereas the life phenomenon is not to be mechanized or rendered merely physical, inconsequential and perfunctory just on account of some of us falling short of penetrating into its complex meanings and secrets.

Architecture is synonymous with physical and spiritual flawlessness, precision and balance. It follows the rules and principles of the perfect universe designed and created by the Perfect Creator. It is a recognition, extension and augmentation of the faultless equilibrium that runs through the veins of total existence. By no means is it imitating, much less challenging or surpassing, the latter. Indeed, there can be no imitation or challenge between two completely different domains with different existential qualities and spheres of influence.

Also, Islamic architecture is a mixture of the heavenly and terrestrial factors and elements. Both sides are extremely important, playing their respective roles. They finely complement and add to each other’s strength and operation. Neglecting either of the two poles in Islamic architecture inevitably leads to a serious damage in its fundamental nature, at a conceptual or a practical level. The heavenly or divine factors give Islamic architecture a soul, moral fiber and its conspicuous identity. They present it with a special aura that Islamic architecture effortlessly exudes inside as well as outside its ambits.

The terrestrial factors, on the other hand, impart about Islamic architecture an intuition about its compelling worldliness, simplicity and utter practicality and pragmatism. They provide a powerful feeling about Islamic architecture’s and its users’ congenital mortality, so nobody should get carried away and, deceived, treat architecture or his self differently. Even though Islamic architecture is inspired and deeply rooted in a transcendental idea and message, it still operates and is greatly influenced and shaped by the exigencies of space and time factors and experiences.

It is certainly because of this that Stefano Bianca remarked on the extent to which the Islamic spirituality influences Islamic architecture: “Compared with other religious traditions, the distinctive feature of Islam is that it has given birth to a comprehensive and integrated cultural system by totally embedding the religious practice in the daily life of the individual and the society. While Islam did not prescribe formal architectural concepts, it molded the whole way of life by providing a matrix of behavioral archetypes which, by necessity, generated correlated physical patterns. Therefore, the religious and social universe of Islam must be addressed before engaging in the analysis of architectural structures” (Stefano Bianca, Urban Form in the Arab World, pp. 22, 23).